Lane Fortenberry | January 23, 2024

Allowing children to help out in the classroom supports their learning and development, according to the findings of a new study coauthored by Texas State University researcher Kiyomi Sánchez-Suzuki Colegrove, Ph.D.

Colegrove, an associate professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at TXST, and Molly McManus, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Child & Adolescent Development at San Francisco State University, led the study.

They published their findings recently in a paper titled, “Can I Help You? Supporting Equity, Learning, and Development by Allowing Children to Help Out,” on the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) website.

The researchers argue that children generally want to help their siblings, parents, and friends outside the classroom and that the same behavior could be replicated inside the classroom — with the buy-in of educators.

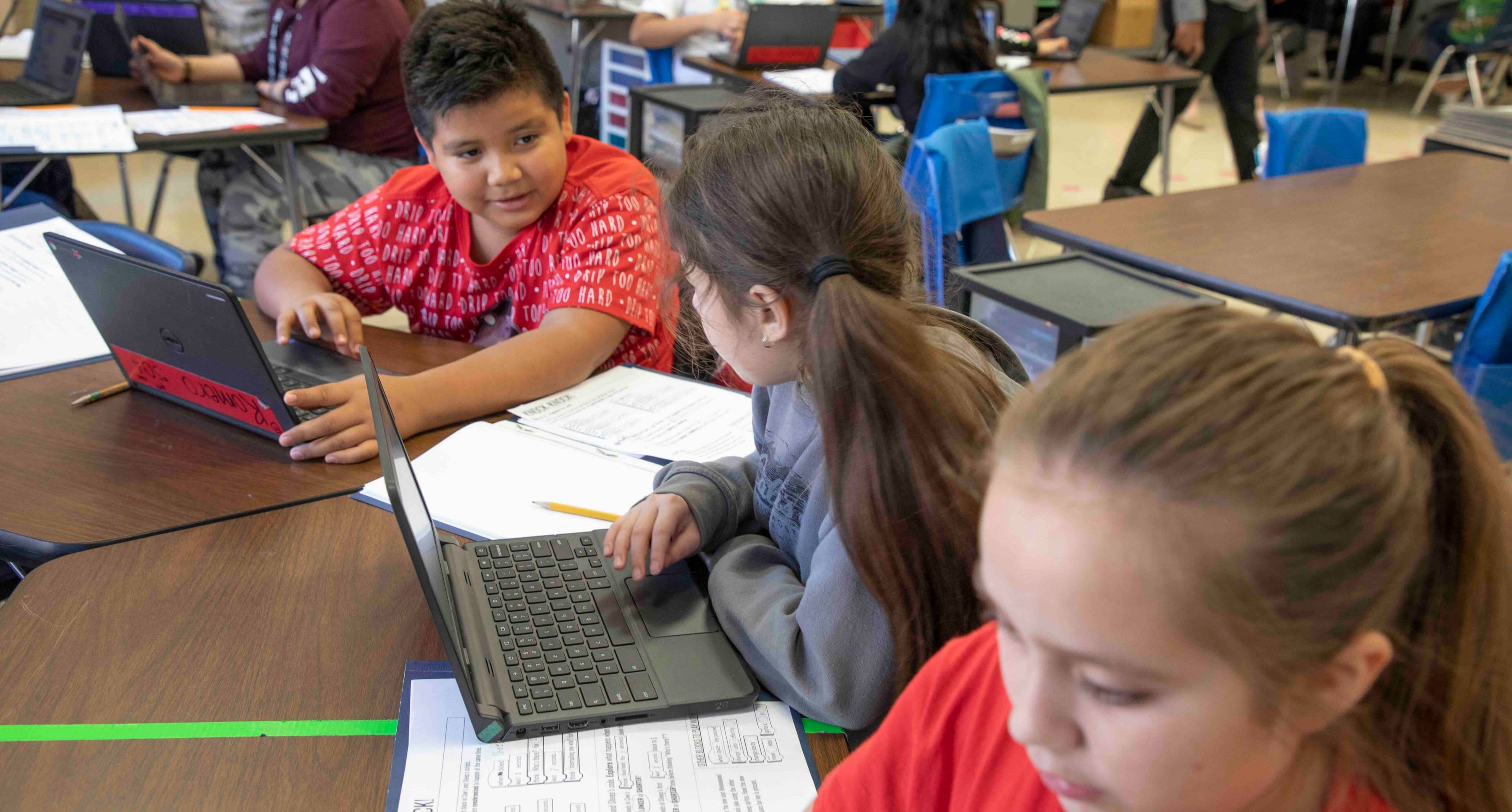

Over several years, Colegrove and McManus spent time in classrooms from preschool to third grade using video-cued ethnography and field work including observations (a qualitative method used in social and behavioral sciences for collecting data) and focus group interviews. They did this to learn from the everyday schooling experiences of young Latine bilingual children. The authors used the term “Latine,” a term created by LGBTQIA+ Spanish speakers that’s intended to be inclusive.

“Kids learn so much by helping out,” Colegrove said. “There are some challenges, like teachers have a lot to teach in terms of curriculum with very little time to do it. With our findings, we wanted to make a piece that can give practitioners some ideas and thoughts on how they can promote helping out in their classrooms.”

Many of the classrooms where they conducted their study included environments that the teachers cultivated to welcome and trust children to make decisions in their learning and to be contributing community members.

“We noticed, especially with bilingual students and children of immigrants, that they do this a lot in the schools, and that’s something parents notice,” Colegrove said. “They’re solving problems, teaching other children, and demonstrating they care.”

Children may lose the desire to help when they’re not allowed to contribute, Colegrove explained. For example, if someone spills a cup of milk, an adult may opt to clean it themselves because the child may not clean it perfectly and would require twice the effort. The researchers argue that allowing the child a chance to clean the milk fosters the development of leadership.

During their study, Colegrove and McManus observed several classrooms with different demographics and social economic status. This allowed them to document the increased levels of noise and allowed movement in classrooms in more affluent, white neighborhoods and compare those with more restrictive classrooms with children of color.

“If you are not allowed to get up from your desk to help someone, then it’s going to be hard to assist another child across the room,” Colegrove said. “Children told us they like helping out, but they can’t because they are told ‘no’ if they raise their hand. However, they become very ingenious and figure out ways to help each other. They are finding ways to defeat the system that didn’t allow them to do it.

“We interviewed a child when she was in pre-K and then again in kindergarten,” she added. “We asked her if she was able to help her friends like she did the year before. She looked sad when we asked her and explained teachers would say ‘no’ when she raised her hand to help another child. She said, ‘I help my mom in the house with my younger sibling.’ By saying that, she’s telling me that she’s not a bad person and wants to help, but she can’t in the classroom. The point we’re trying to make is that when kids do help, they develop a lot of great skills they’re going to need later.”

Colegrove noted that many studies, especially in developmental psychology, are conducted in a lab setting where they test different skills. Their study shows what can happen in a classroom in real time within real situations.

The subtleness and frequency of the children helping each other was what captured their attention over other aspects of their findings and felt important to bring to the attention of teachers as a pedagogical tool in their classrooms.

“They almost predicted the other children’s need for help,” Colegrove said. “It was beautifully done. We hope teachers can pay attention to that because it’s not something we’re taught in teacher preparation. We’re seeing that this is child initiated.”

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |