Jayme Blaschke | May 9, 2023

Early in his career, legendary photographer Ansel Adams, photographed High Country Crags and Moon, Sunrise, Kings Canyon National Park, California, an image that was not printed until 1979 for a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

With High Country Crags and Moon one of the featured works in a new exhibition at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, Stanford art historian Kim Beil wondered if it might be possible to uncover more of the history behind Adams’ photograph to offer new context to his work. Adams kept meticulous notes on the technical details of his photographs—f/stop, lens, shutter speed, etc.—but was notoriously bad at recording dates. For this photo, Adams once wrote that it dated from approximately 1935, but another source claimed 1932, and even those scant notes omit month or date.

Enter Donald Olson, Texas State University professor emeritus of physics, astronomer and Texas State University System Regents’ Professor. Utilizing his distinctive brand of celestial sleuthing, Olson had previously dated Adams’ famous photographs Moon and Half Dome; Moon and Denali; Denali and Wonder Lake; and Autumn Moon, the High Sierra from Glacier Point. In collaboration with Beil and physicist Ava Pope, a Texas State alumna, Olson determined the date, time and location Adams created his early masterwork.

The team’s findings are published in the June 2023 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine, on newsstands now.

High Sierra legwork

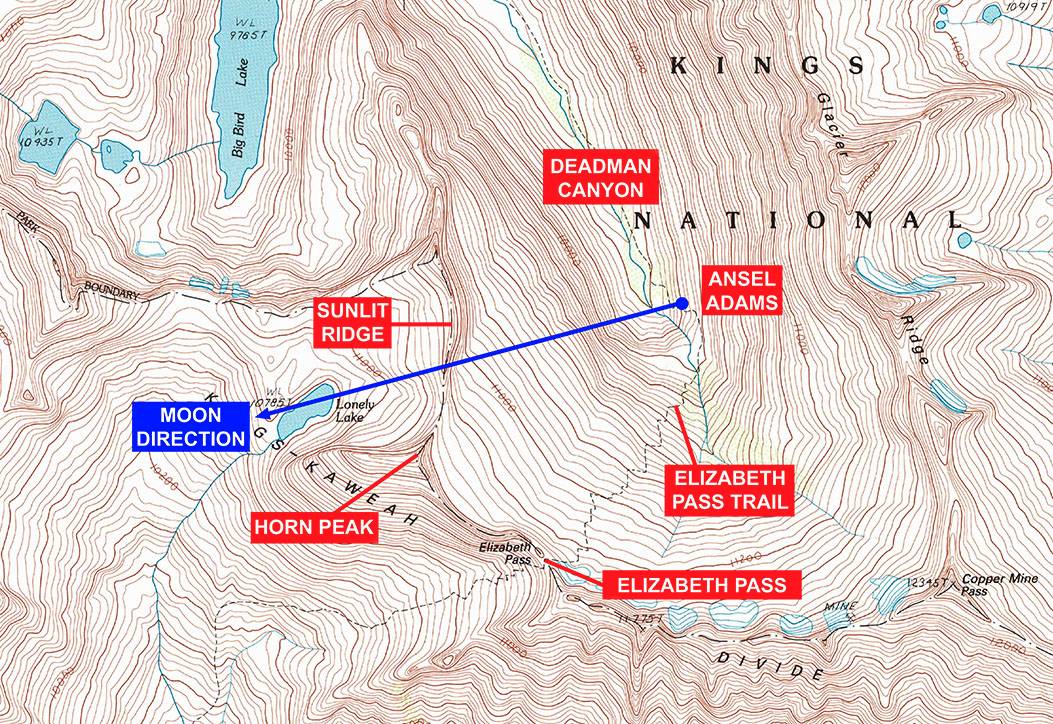

Beil’s first order of business was to determine exactly where in Kings Canyon—a sprawling national park that covers more than 460,000 acres of the Sierra Nevada mountains—Adams captured the image. High Country Crags and Moon depicts a waning gibbous moon in the early morning with sunlight illuminating a granite ridge and sharp crag on the horizon. Because Adams left no notes regarding where he took the photo beyond the fact that it was in Kings Canyon National Park, the exact location remained a mystery. By consulting with experienced climbers of the Sierra Nevada mountains, Beil learned the triangular crag in the photo was likely Horn Peak and the granite ridge could be found at the southern end of Deadman Canyon.

Beil hiked to the remote location and camped overnight in September 2022 to take reference photos for Olson. Based on those daytime and nighttime images, Olson and Pope conducted a topographical analysis showing that Adams set up his tripod near GPS coordinates 36° 36’ 39.3” north, 118° 34’ 6.2” west. Furthermore, an examination of the nighttime photos revealed recognizable parts of the constellations Hercules and Ophiuchus, which allowed the Texas State group to calculate the moon’s altitude and azimuth (or angle in relation to the horizon) coordinates in Adams’ photo – necessary data to determine when the photo was taken.

Libration factor

With a firm grasp on the location where Adams took the photograph and the moon’s position in the sky, Olson could begin looking for potential dates. Olson reviewed all waning gibbous moons from 1923 to 1941. Astronomical software returned four possible matches where the moon was in the correct phase and position. All dates were in the month of August for the years 1923, 1929, 1933 and 1936.

To further narrow down the potential dates, Olson looked to surface features on the moon’s disk and the phenomenon called lunar libration for clues. The moon always presents nearly the same side toward Earth, but wobbles in its orbit so that eventually 59% of the surface can become visible to observers. As captured in High Country Crags and Moon, the moon’s north pole is tilted away from Earth, a situation astronomers call a negative libration in latitude. Taking his cue from that tiny detail, Olson calculated the lunar libration for the four possible dates, looking for a match.

For August 1923 and 1929, the moon displayed a positive libration, ruling those dates out. For Aug. 9, 1933, and Aug. 6, 1936, however, the moon displayed a negative libration. Adams could have captured the scene on either date. Which one was correct?

High trips

Starting in 1901, the Sierra Club held annual outings known as “high trips” to remote areas of the Sierra Nevada for four weeks every summer. Adams joined these expeditions in 1923 and by the 1930s had risen to the position of camp master. Olson searched Sierra Club records and found that the high trip for 1933 was held July 8-Aug. 4, well before the moon’s phase would match the scene in the photography. Furthermore, Adams departed the high trip early on Aug. 3 due to the birth of his son, Michael, two days prior in the Yosemite hospital. Adams then traveled to San Francisco to plan for the opening of a new gallery and was definitely not in Deadman Canyon on Aug. 9, 1933.

For 1936, however, the Sierra Club high trip itinerary and chronicle indicate the outing ran July 11-Aug. 8, including stops to camp in Deadman Canyon Aug. 4-5, and at Lone Pine Meadow Aug. 6. As camp master, Adams was responsible for scouting the new campsite. In the predawn hours the morning of Aug. 6, Adams departed for Lone Pine Meadow—a path that had him traverse the exact location he would’ve needed to be to take the photo.

The moon that morning was in the waning gibbous phase with negative libration, perfectly matching the scene in the photograph. From the moon’s position in the sky, Olson and his team determined that Adams tripped the shutter on his camera at 6:47 a.m. PST on Aug. 6, 1936.

Another moon to sleuth

During his research into the early years of Adams’ career, Olson came across another candidate potentially suitable for astronomical dating. That photograph, Dawn, Mount Whitney, featured a waning crescent moon high in the sky above pinnacles near the summit of Mount Whitney.

The location Adams took the photo was comparatively easy—the trail to the Mount Whitney summit is well-traveled by hikers who post their photos online. The pinnacles in Adams’ photo are known as Keeler Needle and Crooks Peak. Using image data shared by hikers, Olson calculated that Adams set up his tripod near the GPS coordinates 36° 34′ 33.3″ north, 118° 17′ 38.5″ west and at an elevation of 4,300 meters.

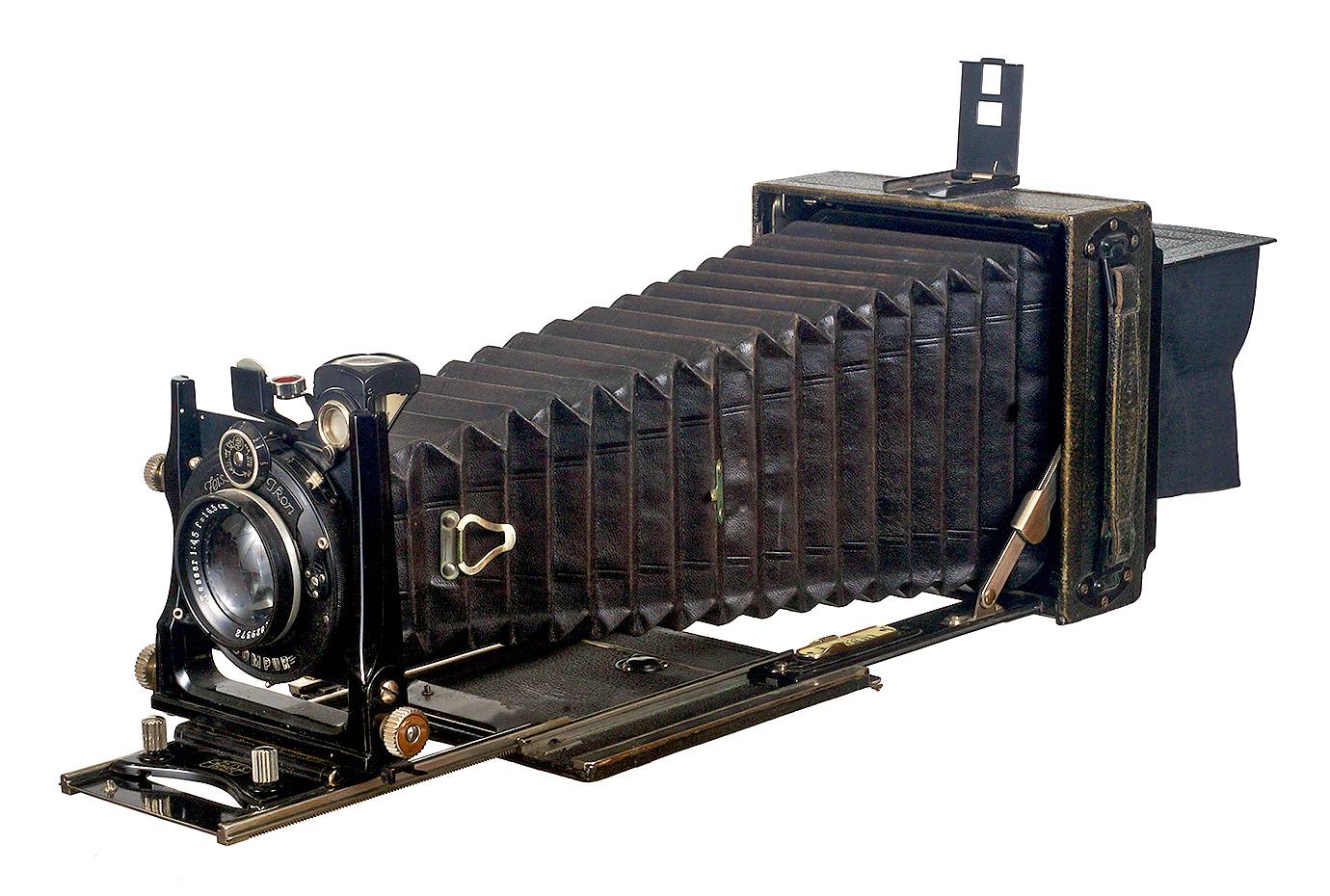

Adams included Dawn, Mount Whitney in an album compiled for the Sierra Club after the 1932 high trip. The original negative of that image indicates Adams used the same Korona View camera for this photo as his famous photo Frozen Lake and Cliffs, also during the 1932 high trip. Olson discovered in the Sierra Club records that the group made base camp at Crabtree Meadow on the evening of July 27, 1932, with a climb to Mount Whitney the in the pre-dawn hours the next morning. From there, the calculations are straightforward—the moon is in the correct phase and elevation and the scene at 4:33 a.m. PST on July 28, 1932, is a perfect match for Dawn, Mount Whitney.

By solving mysteries in art with astronomy, Olson said he hopes to provide more context to the creation process and foster a richer appreciation of nature and human culture.

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |