Jayme Blaschke | October 5, 2022

There are questions throughout history that the average person never considers. Questions such as, “What celestial scene inspired Henry Wadsworth Longfellow while writing his poem The Light of Stars?” “What rare oceanic phenomenon caused the loss of King John’s crown jewels?” Questions such as these, however, spark great curiosity in Texas State University astronomer, physics professor emeritus and Texas State University System Regents' Professor Donald Olson, who has applied his distinctive brand of celestial sleuthing to these historical enigmas, uncovering interesting and even surprising answers.

Olson publishes the findings of these and many other astronomical investigations in his new book, Investigating Art, History and Literature with Astronomy: Determining Time, Place and Other Hidden Details Linked to the Stars.

Longfellow’s The Light of Stars

One of the most popular poets in American history, Longfellow (1807-1882) published his poem, “A Second Psalm of Life: The Light of Stars,” in the January 1839 issue of The Knickerbocker. The poem was subsequently reprinted in Longfellow’s collection, Voices of the Night, as “The Light of Stars.”

Intriguingly, the poem contains multiple astronomical references with the words “night is come,” “the little moon / Drops down,” “the cold light of stars,” “the first watch of night,” “the red planet Mars,” “the evening skies” and “that red star.” Using these clues, Olson suspected he could glean more information about the poem’s creation.

Longfellow himself provided additional clues. In a notebook dated Oct. 6, 1848, Longfellow wrote of “The Light of Stars” that “This poem was written on a beautiful summer night. The moon, a little strip of silver, was just setting behind the groves of Mount Auburn, and the planet Mars blazing in the southeast. There was a singular light in the sky; and the air cool and still.” The phrase “groves of Mount Auburn” is a reference to a wooded cemetery on the west side of Cambridge, Massachusetts, which he moved to in Dec. 1836. As the poem was published in January 1839, the scene that provided Longfellow’s inspiration must have occurred during the summer of 1837 or 1838.

While combing through Longfellow’s letters, Olson came across another clue—Longfellow’s references to the start of summer didn’t correspond to the summer solstice, but rather to the beginning of Harvard University’s summer term, which began in May. This shifted the window of possible dates ahead more than a month in the calendar year.

Armed with this information, Olson and his team calculated planetary positions and phases of the moon following the beginning of Harvard’s summer term in both 1837 and 1838. The astronomical data failed to produce a match for the scene described in the poem for 1837, but those same calculations returned two sets of possible matching dates for 1838: May 24-28 and June 22-27, with the waxing crescent moon on those dates in good agreement with Longfellow’s characterization of it as “a little strip of silver.”

There was a problem, however. The planet Saturn, not Mars, shone brightly in the southeast sky. What’s more, Mars was wholly absent from the evening sky through the spring, summer and fall of 1838, visible only in the early morning, just before sunrise. Saturn, however, was at its closest approach to Earth with its famed rings tilted toward Earth by more than 23 degrees, resulting in an exceptionally bright reflection of sunlight from the planet. This unusual brightness could explain why Saturn caught Longfellow’s attention and helped him mistake it for Mars.

Checking weather records from the Boston area for that time revealed that the dates of June 22-27 did not match Longfellow’s description of “air cool and still,” with temperatures exceeding 80°F. Of the other possible dates, May 24 was relatively warm and cloudy. It rained the evening of May 25, while May 27-28 both featured warm weather.

On May 26, however, the temperature dropped to a much cooler 50°F with clear skies recorded all day long, in good agreement with Longfellow’s descriptions.

Longfellow’s description of the poem’s origin, combined with astronomical analysis and weather records, led Olson to conclude that the inspiration for “The Light of Stars” occurred on May 26, 1838. On this cool evening, as a thin waxing crescent moon was setting, the planet Saturn shone brilliantly in the sky to the southeast. Despite the fact that Longfellow’s poem includes many references to the martial nature of the planet Mars, the poet surprisingly drew his inspiration from Saturn – not Mars.

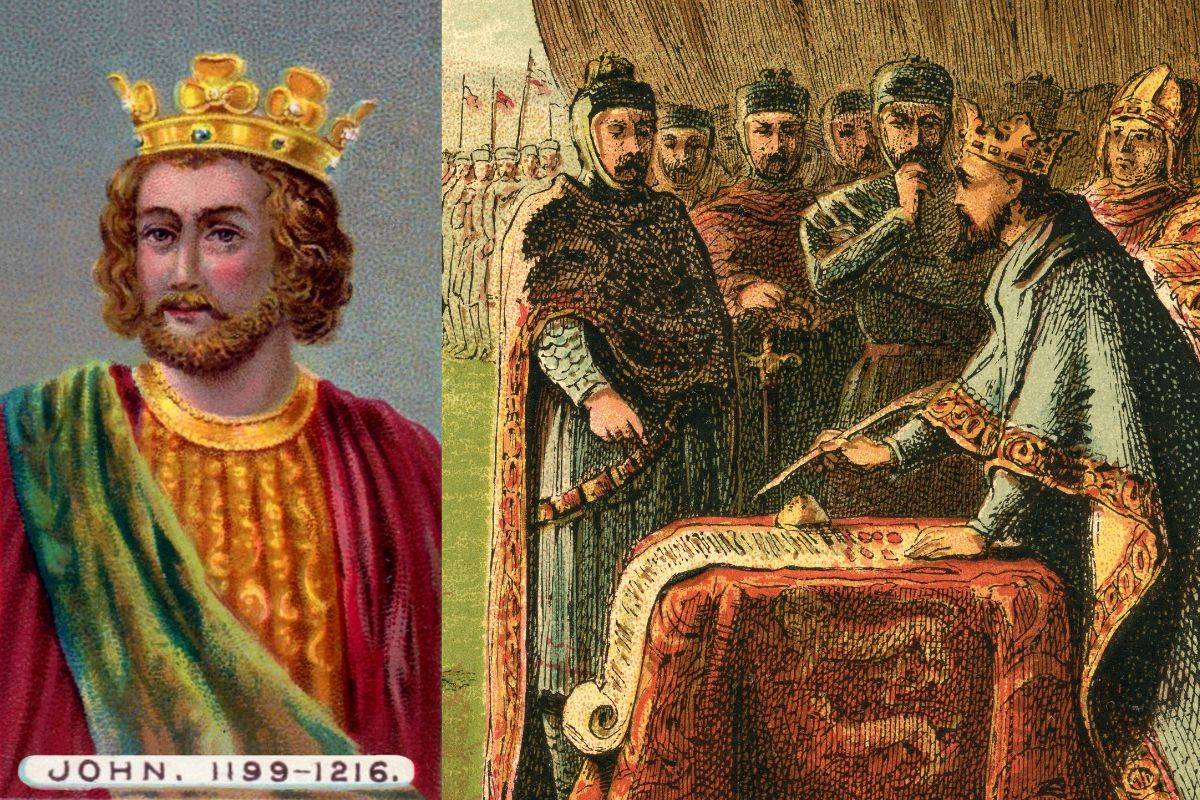

King John and the crown jewels

England’s King John, who lived from 1166 to 1216, is best known to modern audiences as the greedy Prince John in various stories recounting the adventures of Robin Hood. In more formal historical records, he is remembered as the monarch forced in 1215 by rebellious barons to sign the Magna Carta, a foundational document for the United Kingdom’s modern democracy.

Although both sides signed the Magna Carta, neither abided by its terms and civil war broke out. Royalist forces won several victories early on, but a series of reversals had King John on the defensive by autumn of 1216.

On Oct. 12, the king, his entourage, loyal soldiers and baggage train containing the crown jewels departed the town of Lynn (now known as King’s Lynn) along the east coast of Britain for the destination of Swineshead Abbey. Between the king and the abbey lay a bay and estuary called The Wash. Rather than take a more circuitous route around the bay, the king’s company instead opted for a well-known shortcut known as the Wash Way, a sandy expanse passable only at low tide.

The choice initially appeared to be a good one, with the troop making good time. During the crossing, however, the tide rose with alarming speed, turning the solid ground into quicksand. Violent waves overtook the baggage train. Panic seized the king’s party, with some attempting to flee the way they came and others pressing ahead. King John himself barely escaped, finally reaching the abbey late that evening, but the wagons containing the precious crown jewels, provisions for his troops and other valuables had all been lost beneath the surging waves.

Wash Way signified the beginning of the end for King John. Demoralized and nearly bankrupt, he died from dysentery just a week later.

Given that the Wash Way was a well-known route, how was the king’s party caught by surprise by the rising water of the tide? The answer lies in the way the water rose.

Far from the gentle, steady rise of a normal tide, King John’s baggage train was overcome by a sudden onrush of destructive waves. From the descriptions of the phenomenon, Olson immediately suspected the king had fallen victim to a tidal bore.

Tidal bores occur where the rising tide is confined to a narrow, funneled estuary—an accurate description of the Wash Way. In these select locations, a tidal bore appears most reliably near the dates of new moon and full moon. During these periods, the moon, sun and Earth are in alignment so that the gravities of both the sun and moon work together to create unusually high tides, known as spring tides.

Using astronomical software to calculate the position of the moon, Olson discovered a perigean spring tide occurred on Oct. 12, 1216. Not only were the moon and sun in alignment, but the moon was also near the configuration known as lunar perigee and unusually close to the Earth, further increasing the moon’s tide-raising effects. Consulting historical records of other tidal bore events in The Wash, Olson calculated the tidal range that day reached an astonishing 22 feet, with the Wash Way becoming passable shortly before 10 a.m. The devastating tidal bore would’ve appeared in the Wash Way at 4 p.m., subsequently overrunning King John and his forces.

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |