Research collaboration reveals new antiviral function in sense of smell in fish

Jayme Blaschke | July 30, 2019

Researchers at Texas State University, collaborating with a team from the University of New Mexico, have discovered that fish can smell viruses, prompting fast antiviral immune responses.

Irene Salinas, associate professor in the Department of Biology at UNM, is the principal investigator of the study. Mar Huertas, assistant professor in the Department of Biology at Texas State, is co-PI in the National Science Foundation project sponsoring the research. The study, "Olfactory sensory neurons mediate ultrarapid antiviral immune responses in a TrkA-dependent manner," was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and can be accessed at www.pnas.org/content/116/25/12428.

"It is a very exciting discovery because we described a new olfactory function in vertebrates – fish can smell viruses," Huertas said. "Also, we are unravelling the connection between the olfactory and immune system, which can be translated from fish to higher vertebrates. This research can have exciting outcomes for fish vaccination in aquaculture. Half of the fish we find in the market comes from aquaculture, and trout is one of the main aquaculture species in the U.S. In addition, since all vertebrates share common traits in their sense of smell and immune system, this study opens a new area of research in mammal immunology.

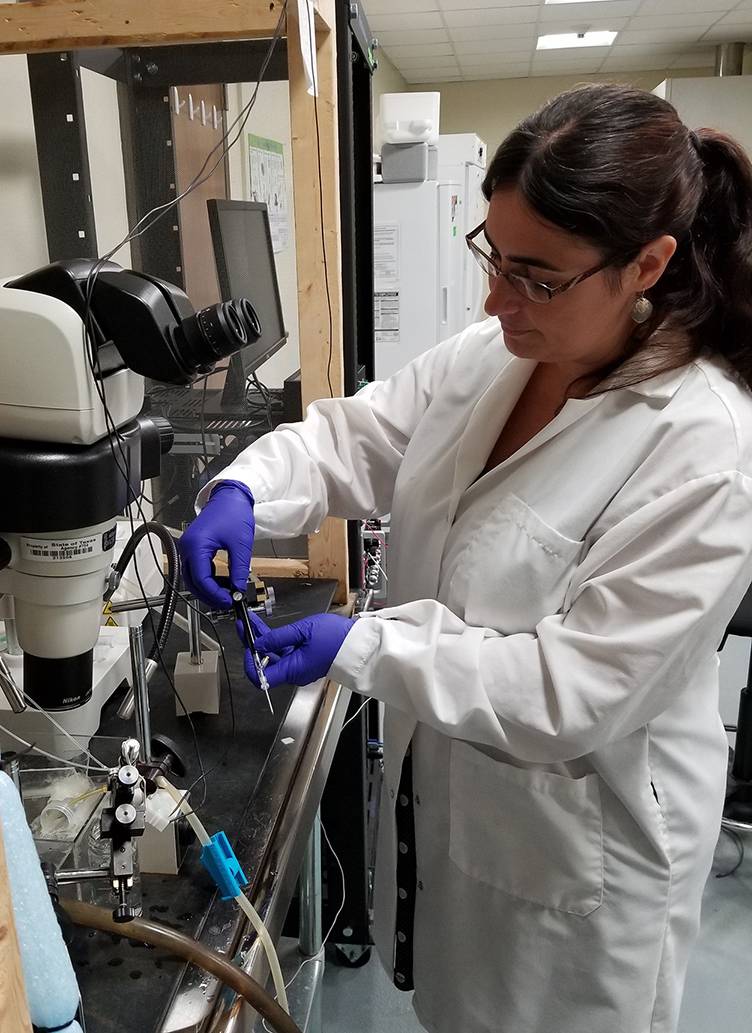

"My role in this research was to show that fish can smell viruses. I’m an electrophysiologist, that means that I can measure the electric responses of the nervous system in an animal," she said. "The nose of any vertebrate (including fish) contains olfactory sensory neurons that expose their sensitive cilia to the external media. These cilia can detect specific odorants, like perfume or food, and when this happens the olfactory receptor is activated and sends an electric signal to the brain, where the information is integrated."

For the study, Huertas exposed the nose of a trout to a live attenuated infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV). She recorded the neural responses, capturing the instant electric responses of the fish nose after the detection of the pathogen – direct evidence that fish can detect pathogens with their sense of smell. Huertas also demonstrated that a drug for a specific receptor in the nose (the TrkA-like receptor), inhibited the fish virus responses.

"I’m currently characterizing the electric signals in the brain after exposure to IHNV," Huertas said. "My graduate student, Fabiola Mancha, is tracing a map that visualizes the neuroimmune connection from nose to the brain using fluorescent dyes combined with the IHNV. In the future, I aim to characterize the neural signals (neurohormones) that can activate the brain immune system."

These findings shed new light on immunological responses in vertebrates and could influence the design and delivery of future nasal vaccines. The research is funded by the United States Department of Agriculture and a 2018 National Science Foundation grant.

Other contributors to the research study included Ali Sepahi, Salinas Lab, UNM; Aurora Kraus, Salinas Lab, UNM; Elisa Casadei, Salinas Lab, UNM; Cecelia Kelly, Salinas Lab, UNM; Christopher Johnston, associate professor in the Department of Biology, UNM; Pilar Muñoz, professor in the Department of Animal Health, University of Murcia, Spain, and Victoriano Mulero, professor in the Department of Cell Biology and Histology, University of Murcia, Spain.

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |