Geographies of the Holocaust

Julie Cooper | January 24, 2019

In recognition of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27, the United Nations “urges every member state to honor the 6 million Jewish victims of the Holocaust and millions of other victims of Nazism and to develop educational programs to help prevent future genocides.”

This spring semester will find Dr. Alberto Giordano of the Texas State University Department of Geography teaching a class in the Honors College with the title: Geographies of the Holocaust and Genocide.

In 2007 Giordano attended a summer workshop at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Over a two-week period, he and fellow academic researchers came together to discuss how geography, mapping, and geo-visualization can shed new light on the Holocaust. From that workshop was born the Holocaust Geographies Collaborative, which continues to this day. In addition to founding member Giordano, principal investigators of the group are: Tim Cole, the University of Bristol; Paul Jaskot, Duke University; and Anne Knowles, the University of Maine. Maël Le Noc, a Texas State Ph.D. student, is also affiliated with the collective.

Groups that have funded the collaborative’s projects include: the National Science Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Holocaust Educational Foundation, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure, and the Shoah Foundation.

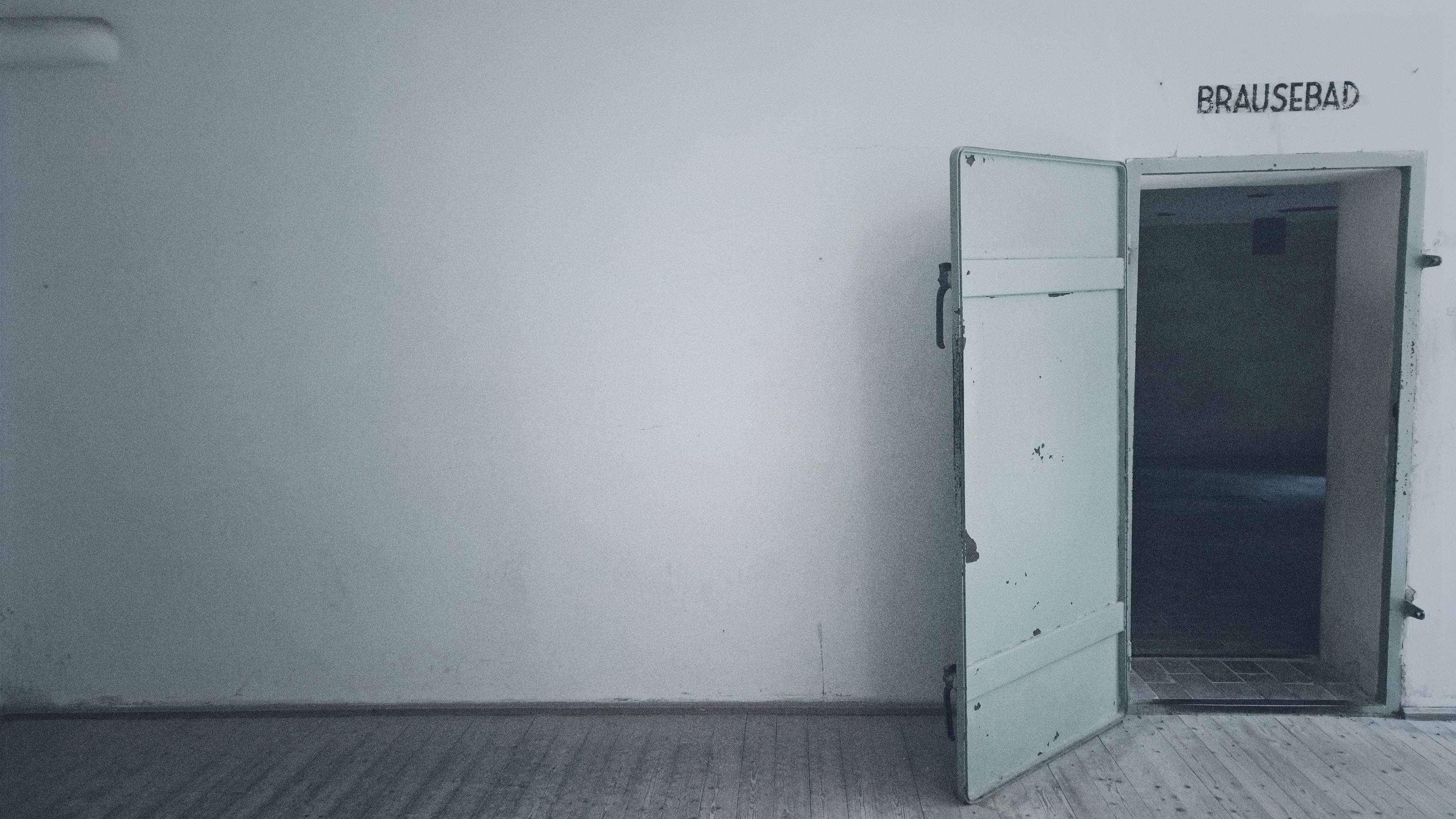

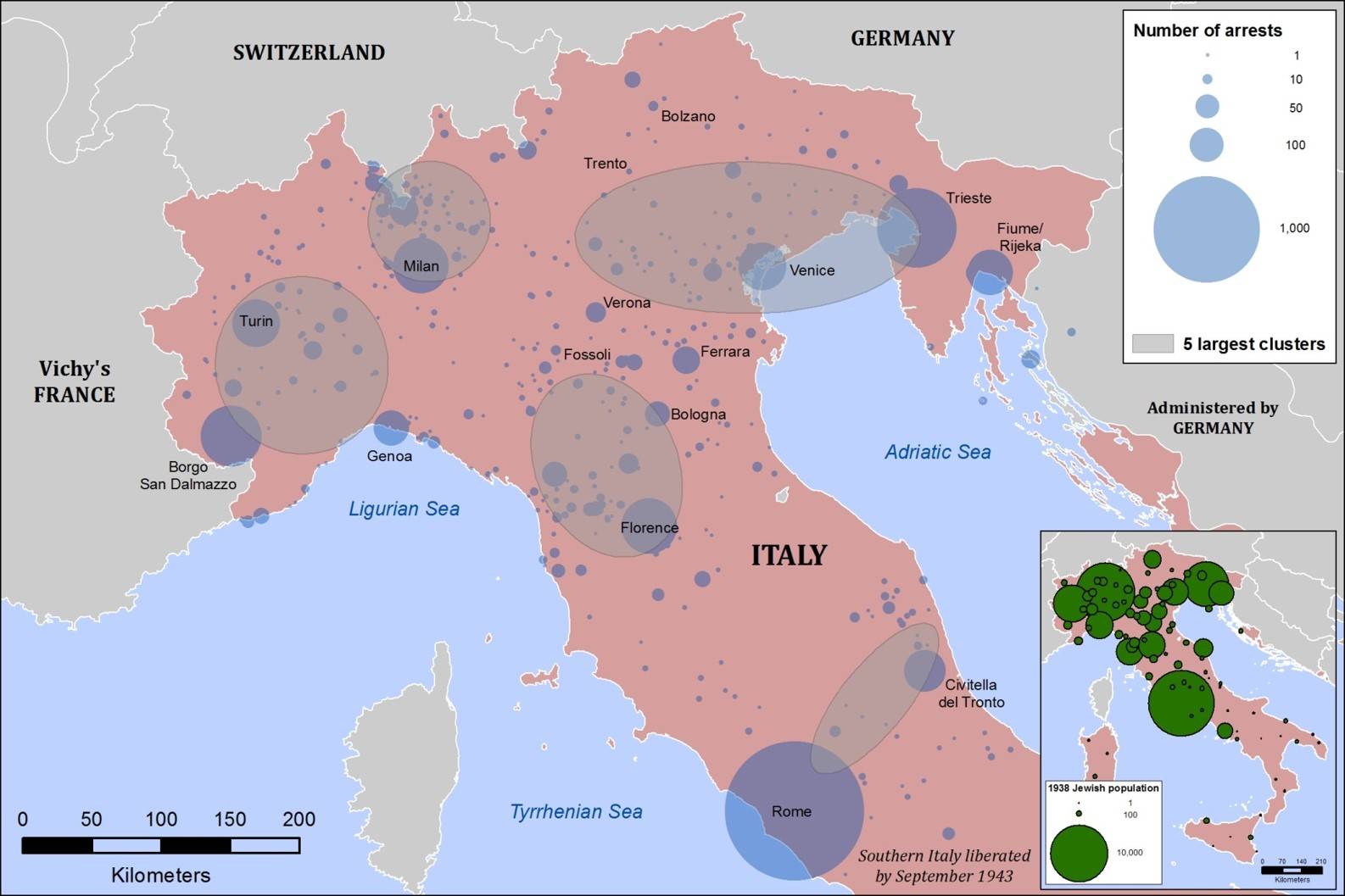

These projects have resulted in a series of edited volumes, book chapters, and journal articles centered on a number of case studies examining the spatial realities of the Holocaust, using illustrated maps and graphics to show how the genocide was planned, organized and executed. Resources produced include maps showing the opening and closing of concentration camps, the arrest locations of Jewish Holocaust victims in Italy (including personal information such as name, age, and gender), and evacuation routes taken by camp prisoners on fatal “death marches” at the end of the war. There are also more intimate analyses of the layout of the Auschwitz concentration camp, ghettos in Budapest, and how camp guards arranged themselves spatially in order to maintain control of prisoners and facilitate the brutal efficiency of the Nazi death machine.

“In the last year we have moved to qualitative data and qualitative methods,” Giordano says. “In particular, we are looking very closely at the testimonies of survivors of the Holocaust. One thing I am very interested in is social networks — how families and communities are broken up, destroyed, and reconstituted as a result of their genocide experience, and how victims survive the Holocaust as a result of spatial strategies and the social networks they are able to establish.

“At the moment, I am working with a database of about 70,000 survivors in Budapest. Who are these people? Where did they come from? (Many were not from Budapest.) Who were they living with, including their immediate family, their friends from the village? Who else? In which ways did the Holocaust reconfigured the traditional Jewish nuclear family for the purpose of surviving genocide?

“Our aim is to show that geography matters and that we can bring a different understanding to the Holocaust by changing the geographical lens of analysis: from the individual to the family, from the village to the city, from the camp to the ghetto, the experience of the Holocaust unfolded differently for different people at different places at different times,” he says.

Giordano, who joined Texas State in 2003, recently received a Fulbright Scholar grant to Lithuania, where he will apply geographical methods and perspectives, including the use of GIS, to a larger project on the historical geography of Jewish Lithuania.

World War II and the Holocaust, he says, changed the geography of Eastern Europe forever, with the disappearance of thousands of communities and the loss of millions of people, Jews and non-Jews alike.

“I think that studying the Holocaust is important in the context of other genocides, to understand how they may happen and, hopefully, what we can do to prevent them,” he says.