From segregation to integration: The first Black students at Texas State University

February 7, 2020

“‘We the people,’ it is a very eloquent beginning. But when the Constitution of the United States was completed on the 17th of September 1787, I was not included in the ‘We the People.’ I felt for many years that somehow George Washington and Alexander Hamilton just left me out by mistake.” – U.S. Rep. Barbara Jordan

It was quite a different time and place in mid-20th century Texas. Although the civil rights movement was sweeping the country, many public colleges and universities, Texas State included, were slow to integrate.

School Integration in Texas

In February 1946, Herman Marion Sweatt was denied admission to The University of Texas Law School; he met all eligibility requirements for admission except for his race. His lawsuit, Sweatt v. Painter, would eventually change the course of graduate education and the state’s interpretation of “separate but equal” facilities. The U.S. Supreme Court later ruled in Sweatt’s favor, and he and other Black law students gained admission in 1950-51.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that separate public schools for Black and white children were unconstitutional; and the doctrine was extended in 1956 to state-supported colleges and universities. The University of North Texas admitted Black students to the freshman class in 1956, but they were not allowed to live on campus. The University of Texas System Board of Regents announced all qualified applicants would be admitted to UT Austin by September 1956. But in that same year, Texas Gov. Allan Shivers led the fight against integration when he ordered state police to prevent the court-ordered desegregation of Mansfield High School in Tarrant County.

Texas State University

In 1962, Dana Jean Smith, an 18-year- old Black woman, applied for admission to what was then called Southwest Texas State College. A graduate of Austin’s Anderson High School, Smith was academically qualified to enroll in the college. President John G. Flowers, in a letter dated June 22, 1962, said Smith’s application was rejected because of the whites-only provision in the charter establishing the college. He also informed her that only an act of the state Legislature or a court order would make it possible for Smith and other Black students to be admitted.

A similar letter was sent to another young Black woman who applied, Mabeleen Washington. “We had met all the requirements, but ‘we were of the Negro race,’” she said. “I wanted to go to college really, really bad. My dad told me he wouldn’t pay for college out of town.”

Daniel Smith, Dana’s father, retained lawyer J. Phillip Crawford who filed a lawsuit in August 1962 in U.S. District Court in Austin. A class action suit was initiated on behalf of all qualified Black students; defendants of the lawsuit included Flowers, Registrar Clem Jones and (what was then called) the Board of Regents, State Teachers Colleges of Texas.

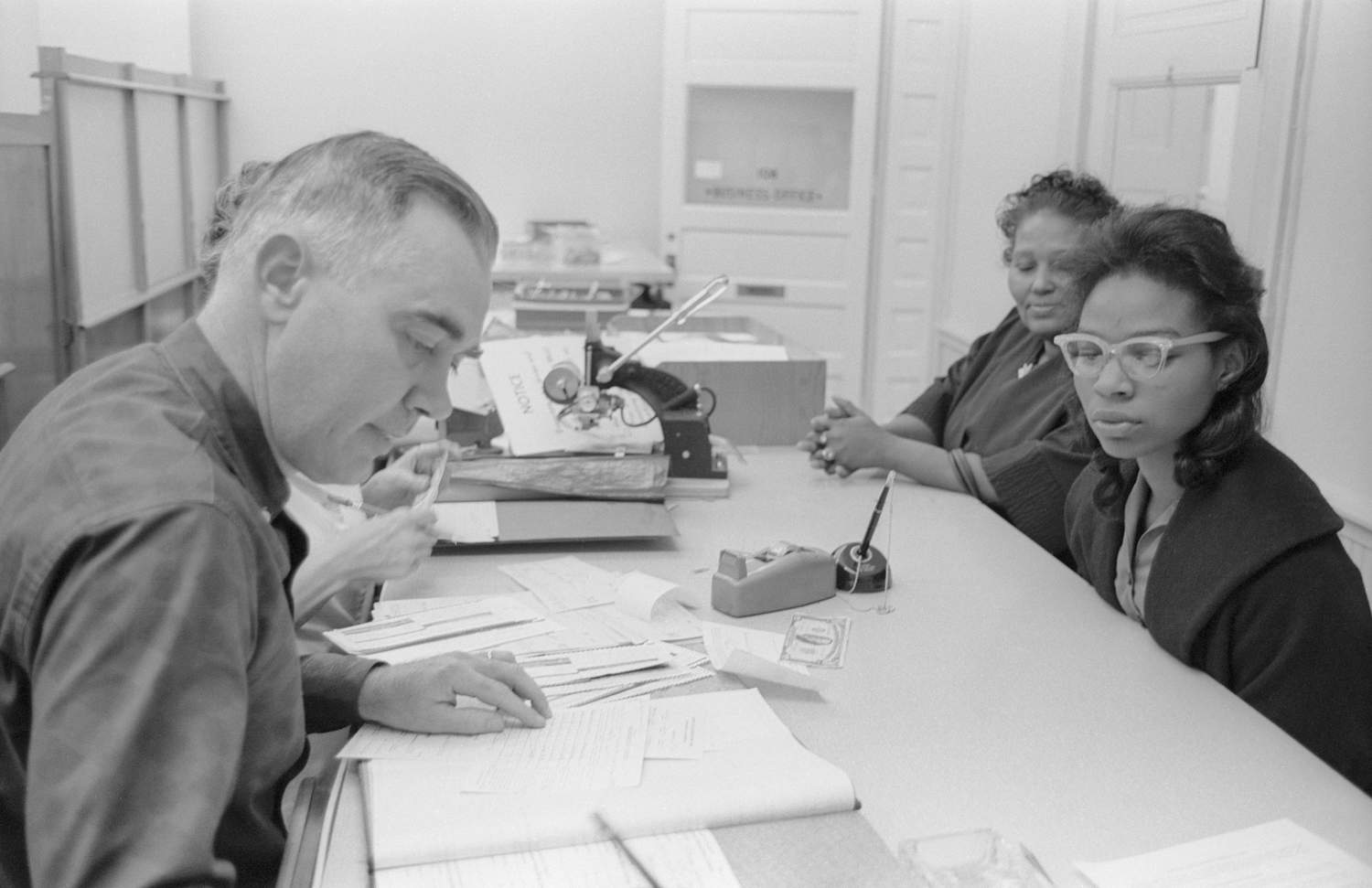

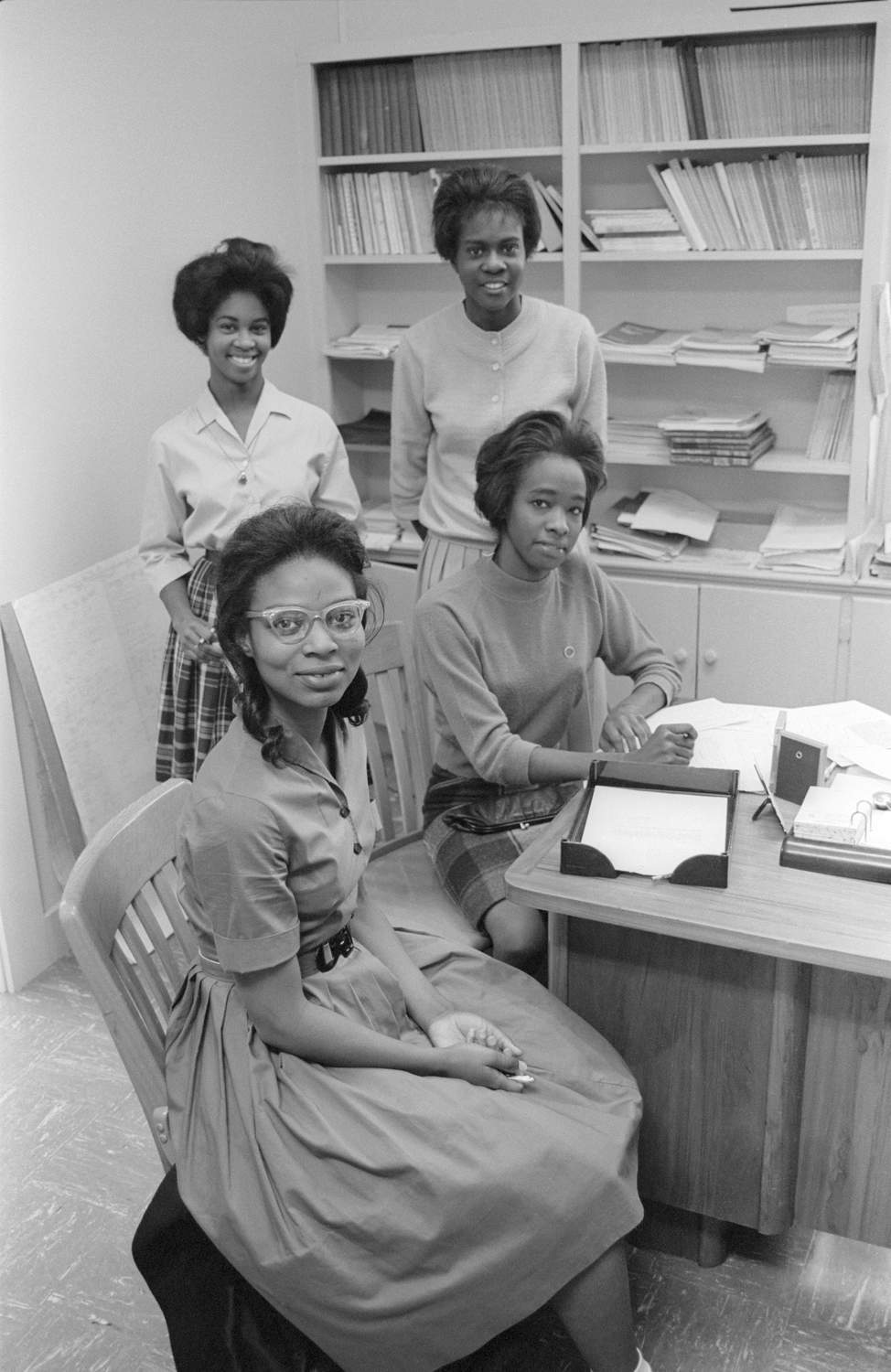

On Feb. 4, 1963, U.S. District Judge Ben H. Rice Jr. signed the court order that ended segregation at the university. By 3:15 p.m. that day, Smith and three other Black women from San Marcos − Georgia Faye Hoodye, Gloria Odoms and Mabeleen Washington registered for classes. The following day, Helen Jackson, a sophomore transfer from Huston-Tillotson College, also enrolled.

They made history as the first Black students to attend Texas State. And a little more than 50 years later, they made history again when the five women reunited on the San Marcos Campus for the first time to take part in a discussion on their experiences and how they helped shape integration at Texas State.

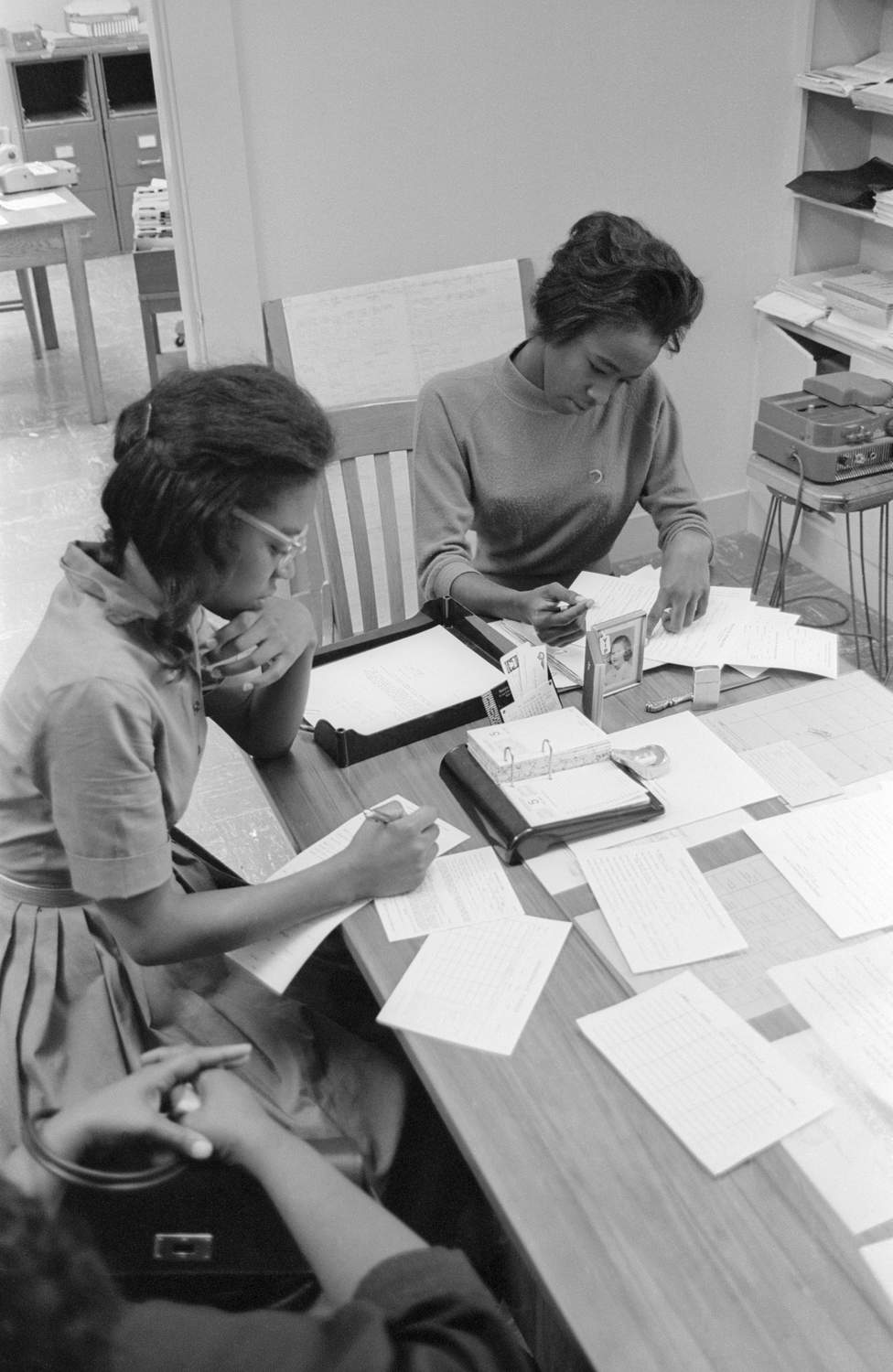

The women enrolled at Texas State in 1963, following a changing tide of sentiment that led to the integration of many public schools and universities across the country. Still, resistance lingered and posed challenges at times.

Wozniak says her adjustment problems were reflected in her grades. In high school she was an A/B student but says her grades in college slipped. “Whatever it was, I overcame it later,” she says. “I had a dream of being a nurse.” She married and left Texas State after one semester, but eventually graduated at the top of her class in pursuing her associate’s and bachelor’s degrees.

Archival accounts from the University Star indicate that integration at Texas State took place without the protests and violence that marked the situations at schools in other Southern states. A Star article noted that residence halls remained segregated and all five women lived with their families, not on campus.

For several of the young women, the university was “close to home.” Franks said her father owned a business in San Marcos and it was “much easier to be home and eat home-cooked meals.”

When asked where they found support on or off campus while attending Texas State, the five women agreed: It was family and the Black community that gave the most support. But there were individuals too − Powell credited her high school librarian who paid for some of her textbooks. Smith praised Dean of Students Martin Juel for his support and called him “our on-campus daddy.” She also recalls that then University President John Flowers “always knew how we were doing academically. He knew people’s names and faces.”

Franks says her grandmother was her biggest supporter. Powell remembers a saying her mother used: “You’re no better than anybody else, but there’s nobody any better than you.” Cheatham says her mother, who finished eighth grade, pushed her to succeed saying “you must get an education.”

A few of the women offered advice to current students facing adversity.

“Remember, your worst day is only 24 hours long,” Smith says.

“When you go to class, go to learn not socialize,” Powell says.

“Hang in there,” Cheatham says. “Trust yourself, don’t let anything stop you.”

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |