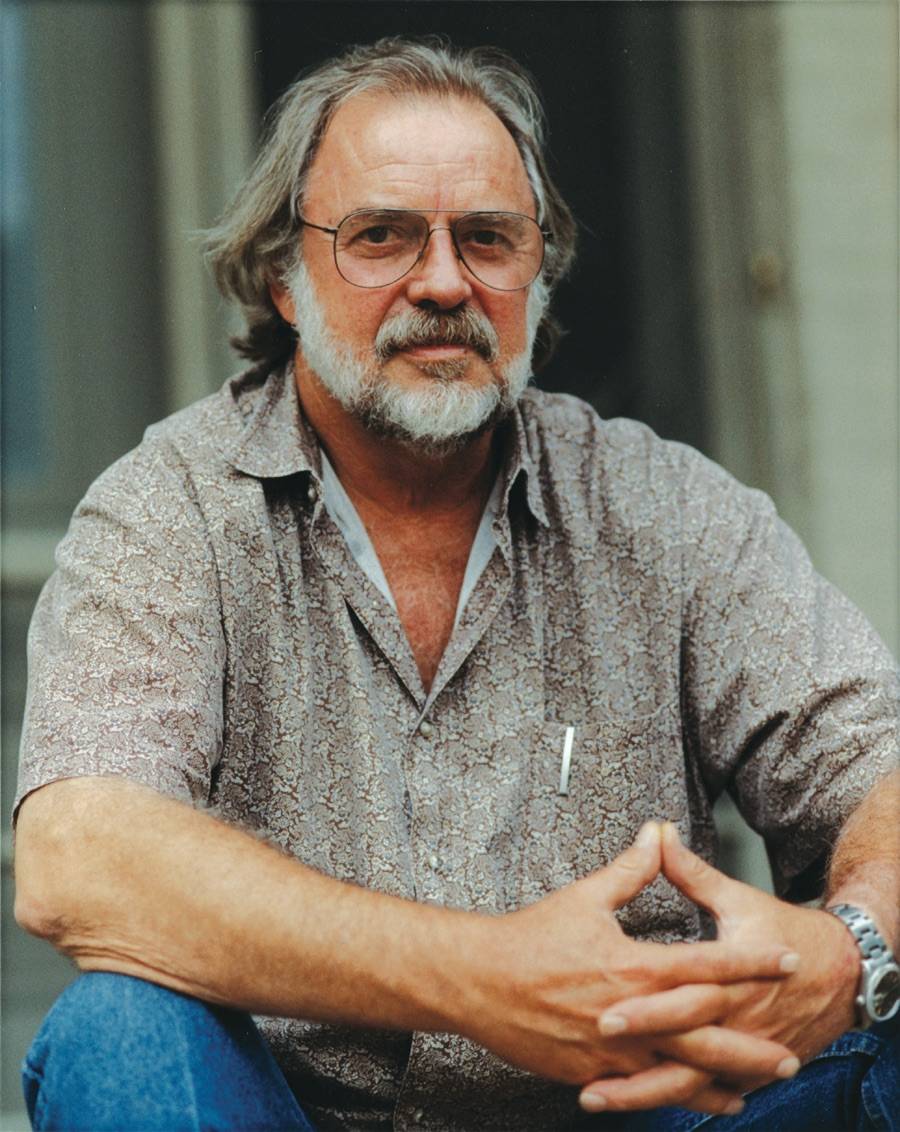

In Memory of Bill Wittliff

Written for Bill Wittliff by Stephen Harrigan | July 3, 2019

Bill Wittliff, a Texas State Hero, and a dear friend of Texas State University, passed away on June 9, 2019. Bill and his wife, Sally, founded The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in 1986 to create a special collections research archive, library, and exhibition gallery focused entirely on the creative spirit of Texas and the Southwest. Because of their continued support, today The Wittliff includes more than 500 special collections in literature, photography, music, and film, and attracts visitors, researchers, and lifelong learners from around the globe. It stands as a tribute to Bill’s legacy.

Bill Wittliff was, among so many other things, one of the most successful screenwriters in the world. He knew how to braid a confusing tangle of events into a single coherent narrative, or one central theme. I’d like to be able to do that today, but Bill’s life was too various, too vast, and too crucial to everyone here that it almost seems like an insult to his memory to try to neatly sum up who he was. There’s no one Bill Wittliff story—there’s a story for each of us.

And just as there’s no one story to his life, there’s no one theme. But there are three words that keep cycling through my mind when I think about him and what he meant to me and I suspect to most of you: the three words are integrity, inspiration, generosity.

These three elements of his personality weren’t separate, they weren’t sequential, they were all bundled together into a human being you instinctively liked and trusted and, maybe at some level, found yourself wishing you could be. That was certainly my first reaction to being in Bill’s presence. I had bumped into him from time to time in the late 1970’s but had my first real conversation with him sometime around 1980 at a party at Anne and Robert Barnstone’s house, an event that turned out to be one of the most important evenings of my life.

I remember sitting with him on the Barnstones’ patio for an hour or more, with the chatter of the party fading into the background while the two of us talked about the craft of writing.

At that point in my life I was a confused young writer, struggling not just with how to express myself in words, or how to make a living doing it, but—even more crucially-- how to be the person I wanted to be. In my heart I feared I was nothing much more than a groveling yes-man, too ready to grasp at any opportunity to get ahead, too eager to please anybody who would condescend to notice me.

But here I was, being treated as a peer—as a friend even—by the most confident and self-possessed person I had ever met. I wasn’t sure why he was being so welcoming. I didn’t yet know that that was just the way Bill was. He had a way of seeing something in you that you didn’t necessarily see in yourself.

He was one of the funniest people I’ve ever known, and hands down the greatest story teller, but I don’t remember laughing or joking with him that night on the patio. What I remember is one of the most open and earnest and generous conversations I’d ever had with anyone.

It was a conversation that continued for forty years. Some of you have known Bill longer than that, some of you have known him better than I have, but I bet we can all agree that we’ve never known anyone else like him.

He had such a clear-headed sense of himself. He was someone who was never afraid to say no, but whose door was always open. You knew when you listened to him talk that he came from someplace real, and you knew by every choice he made that he stood for something

Important. He was a living rebuke to inanity and pretense. He knew what was true, and he was relentless in sniffing out anything that was bogus.

When something mattered to him, and so much did, he was uncompromising. When his movie Barbarosa was released, he was so appalled by the edited version that was shown in theaters that he convinced the studio to give him back all the dailies, and he hired Eric Williams, who was then a UT film student, to spend a year in his office on Baylor Street re-cutting the movie into a form he could live with. Time and again, his friends at CAST, the committee we had formed to create statues in Austin, including one by Clete Shields of Bill’s great friend Willie Nelson, would watch in awe as he would probe and ponder, questioning whether we had chosen the right subject, hired the right sculptor, not yet found some elusive flaw in the piece’s modeling or placement. He never let us cut corners, especially not for a monument that was going to last hundreds of years.

None of this was empty perfectionism. It was an insistence on truth, and it pervaded every aspect of his artistic life, every moment of his interactions with other people.

It was certainly this insistence that elevated Lonesome Dove from what could have been a fairly conventional cowboy miniseries to the most beloved western ever made. As the project’s screenwriter, executive producer and guardian angel, he made sure the movie was made in a manner that honored Larry McMurtry’s novel and protected the adaptation from wrongheaded casting and sometimes boneheaded studio notes. “If we take care of Lonesome Dove,” he told everyone involved with the production, “Lonesome Dove will take care of us.”

When I look back on my friendship with Bill, maybe the most memorable moment was on a day I visited the Lonesome Dove set near Del Rio. The filmmakers were about to shoot the scene in the script in which Tommy Lee Jones as Woodrow Call and Robert Duvall as Gus McCrae lead the Hat Creek outfit across the Rio Grande into Mexico to steal horses.

“Come with me,” Bill said as the shot was being set up. He led me down a cutbank to the edge of the water. It was twilight, the time of day known as the magic hour in filmmaking, when the light is rich and fading. The river where we stood was the actual Rio Grande, and the costumes and saddles and firearms the actors were outfitted with were—according to Bill’s demands-- rigorously authentic. After the director called Action, there was an odd silence as the men led their horses into the water toward Mexico—nothing but the sound of splashing, the creak of leather, the calls of redwing blackbirds in the reeds along the shoreline.

While this was happening, Bill turned to me with an astonished grin. Neither of us needed to say anything. We both knew we were not just watching a movie being made but something both real and dreamlike taking place before our eyes.

The picture that Bill took at that moment is “Crossing the Rio Grande,” one of the most evocative of his famous Lonesome Dove photographs. I have that photo on my office wall, courtesy of course of Bill, and every time I look at it, which is every day, I remember that magic hour on the Rio Grande and the great friend who invited me to share it with him.

It was these moments of alchemy, of fellowship, of creation, that his life was all about, and what his legacy is about. And it’s not just hislegacy. The week before he died, Bill and Sally had celebrated their 56thwedding anniversary. They met in 1960, after Bill saw Sally’s picture in the UT yearbook and decided then and there that he was going to marry her. He probably had no idea at the time what he was getting into; what a powerhouse mind and spirit there was behind that Bluebonnet Belle façade, but he soon found out. It was Sally who decided one day to look up J. Frank Dobie in the Austin phone book, march up to the house of the writer whose work had ignited the teenage Bill Wittliff’s imagination, and say, “Mr. Dobie, will you sign a copy of your book for my boyfriend?” Sally was his partner in creating the great Texas cultural heritage that lives on through his work and through the Wittliff Collections.

Speaking of the Collections, I want to close with something I read last week, a few days after Bill died. Of all the hundreds of expressions of grief and appreciation it was the one that moved me the most, probably because it made me flash back to that long ago evening when I had had the lifelong good luck to talk to Bill and be taken seriously by him.

As I was back then, Christian Wallace is a young writer for Texas Monthly. In a Twitter Post, Christian remembered the time he met Bill at a reading at the Wittliff Collections. They began to talk about writing, and Bill asked him what kind of writer he wanted to be. Christian gestured toward Pat Oliphant’s statue of John Graves that looms over the Collections’ reception area.

“A few days later,” Christian wrote, “I got a call from someone at the Wittliff. She said they had a package for me. I went by and picked up a manila envelope with my name scrawled across the front. Inside was a rusted horseshoe and a letter.”

The letter read “Here’s a horseshoe I found out at John Graves’s Hard Scrabble the last time I was there. . . I believe in Luck. . . now here’s some you can take along with you as you go. . . “

“It was one of the kindest and most unexpected gifts I’ve ever received,” Christian wrote. “For a Texas literature fanboy, it was also one of the coolest. I wrote Bill and he told me to ‘pass it on when you’re an Old Fart.’”

As I said, there’s a Bill Wittliff story for each of us. That was Christian Wallace’s, you’ve heard part of mine, and you’ll hear others today—more stories of integrity, inspiration and generosity. And no doubt after we leave the cemetery this morning we’ll all be telling Bill Wittliff stories on into the afternoon, far into the night, and deep into the ages.

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |