The Road to April 4: MLK and the Memphis Sanitation Strike

January 24, 2020

An essay by Dr. Dwonna Goldstone, Associate Professor of History/Director of the African American Studies program at Texas State University

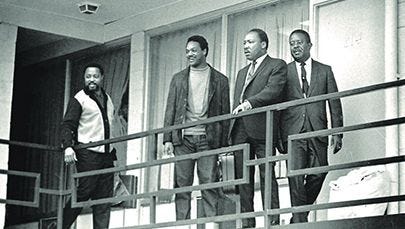

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. King had come to Memphis the day before to again show his support for black striking sanitation workers, who were working under grossly hazardous conditions and receiving significantly lower wages than their white counterparts.

Baxter Leach, a sanitation worker in the 1960s, said, “It was hard back in those days. We didn’t have anywhere we could go to the bathroom and nowhere to wash our hands when we got through eating.” Leach also recalled having nowhere to shower after “liquid stench would dribble from the metal tubs” they had to lug to the garbage truck. “We would wear the same clothes back home,” he said.

The black sanitation workers staged their first walkout on Monday, February 12, 1968. The strike was preceded by the deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two sanitation workers who had been crushed in a trash compactor. Some 1,375 men—mostly sanitation and sewage workers but also other employees of Memphis’ Department of Public Works—did not show up for work. Then Memphis mayor Henry Loeb declared the strike illegal and refused to meet with black leaders, although he did meet with representatives of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Local 1733 union.

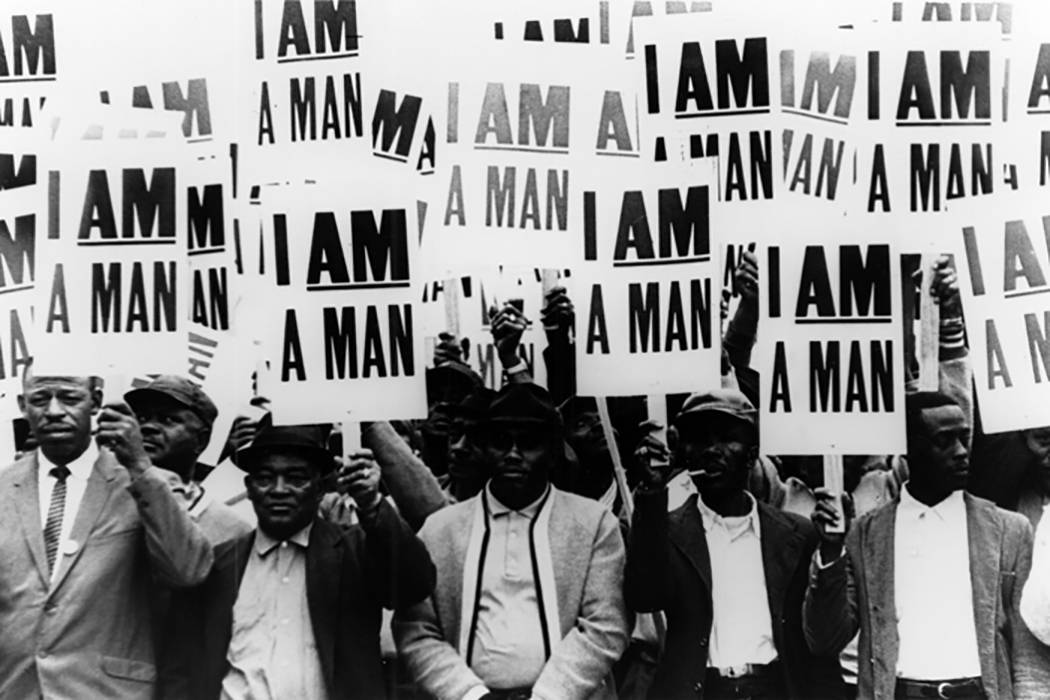

The strike, however, continued. By February 15, some 10,000 tons of trash was piled up around the city, so Mayor Loeb began to hire white strikebreakers who traveled with police escorts. These white strikebreakers were not well received and were often assaulted. Black sanitation workers began to meet each day at noon with nearly a thousand strikers and then marched from Clayborn Temple to downtown Memphis. White police officers attacked the marchers with mace, tear gas, and billy clubs. After one particularly brutal police assault, Reverend James Lawson said, “For at the heart of racism is the idea that a man is not a man, that a person is not a person. You are human beings. You are men. You deserve dignity.” Rev. Lawson’s words are the message behind the “I Am A Man” signs that so many men carried during the strike and subsequent marches.

King came to Memphis on March 18, 1968, where he spoke “to an audience of thousands” at the Mason Temple. King returned to Memphis and participated in a march on March 28, 1968, that turned deadly. Protesters broke out windows, and some held signs that read: “LOEB EAT SHIT.” Police responded with batons and guns. Some 60 others were injured,and police arrested 276 people. Memphis police officer Leslie Dean Jones killed 16-year-old Larry Payne.

King called Payne’s mother and promised her that he would visit, but he would be assassinated before he could. Though the police wanted Payne’s family to hold a private, closed-casket funeral, they instead decided to hold it at Clayborn Temple. More than 600 people—including the students and faculty of Mitchell Road High School where Payne was a student—attended Payne’s funeral. Rev. B. T. Dumas, pastor of New Philadelphia Baptist Church, gave the eulogy, which he titled “Man Is Like Grass And Is Cut Down in Various Stages of Life.” Lizzie Mason Payne, Larry Payne’s mother, was so full of grief that she had to be led from the church. According to The Washington Post, Mrs. Payne said to her son: “They killed you like a dog.” At the conclusion of the funeral, sanitation workers marched peacefully downtown.King would be assassinated in Memphis two days later. As he and other civil rights leaders stood on the second-floor balcony in front of Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel—a room that had been dubbed the “King-Abernathy suite” because the two men stayed in it so often—James Earl Ray shot King at 6:01 p.m. After emergency chest surgery at St. Joseph’s Hospital, doctors pronounced King dead at 7:05 p.m. (More than 50 years after King’s death, many people still believe that Ray was not alone responsible for King’s assassination.) Although civil rights leaders implored black America to maintain the nonviolence for which King advocated, riots broke out in many cities across the United States, including Memphis, Kansas City, New York, Chicago, Detroit, Washington, D.C., and Baltimore.

Four days after King’s assassination, Representative John Conyers (D-Michigan) introduced the first motion to make King’s birthday a national holiday. It would take until November 2, 1983, for his birthday to become a federal holiday, and it would take until 2000 for all 50 states to honor King’s birthday with a paid holiday. Observed each year on the third Monday in January, MLK Day has been transformed into “a day on, not a day off.” According to the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS), MLK Day is the “only federal holiday designated as a national day of service to encourage all Americans to volunteer to improve their communities.” January 20, 2020, marked the 25th year of the MLK Day of Service.

As for the Memphis sanitation workers, their strike continued. Though many in Memphis feared riots would break out following King’s assassination, Mayor Loeb refused to make any concessions to the sanitation workers. On April 8, some 42,000 people participated in a silent march through the city of Memphis; among the participants were leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) and Coretta Scott King, MLK’s widow. Eight days later, the strike would end with a settlement that “included union recognition and wage increases.” In July 2017, Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland announced at the National Civil Rights Museum that the city would “offer $50,000 in tax-free grants to the 14 surviving 1968 sanitation strikers. We’re proposing a new retirement plan, an additional retirement plan for all sanitation employees.” This money would allow for these men to live more comfortably in their retirement years than they had been just living on social security.

For King, helping the Memphis sanitation workers was an extension of his “Poor People’s Campaign,” a plan to bring economic justice to all of America. King and the SCLC had been traveling around the country to “assemble a multiracial army of the poor” that would march on Washington, D.C., to “engage in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol until Congress created an economic bill of rights for poor Americans.” He wanted federal and state governments to invest in rebuilding cities, and in his book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? King advocated for a guaranteed basic income, a policy proposal that is the center of 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang’s campaign. Toward the end of his life, King worked tirelessly to bring an end to the Vietnam War, a position that alienated others in the civil rights movement who worried that these new positions would “accelerate the backlash and repression on the poor and the black.”

King did what he could to change the hearts of white America; in fact, he gave his life to the cause. Though some argue that Barack Obama’s ascension to the presidency marked America’s movement into a post-racial state, it did not. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), the “number of hate groups operating across America rose to a record high—1,020—in 2018.” In fact, it was the “fourth straight year of hate group growth.” Not surprisingly, racist and antisemitic violence continues to “plague the country,” and FBI statistics show that “hate crimes increased by 30 percent in the three-year period ending in 2017.” In Texas,however, the number of hate crimes being committed is even more staggering. FBI data shows that from 2017 to 2018, hate crimes increased by 139%—from 190 hate crimes to 455 hate crimes. These, of course, are just the number of hate crimes that have been reported.

King once said, “The ultimate tragedy is not the oppression and cruelty by the bad people, but silence over that by good people.” On this holiday honoring MLK, my hope is that white Americans will join people of color to finish the work started by King and other civil rights activists.

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |