Say goodbye to Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben

Julie Cooper | June 22, 2020

Saying goodbye to racially stereotyped images on popular consumer products like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben is among the latest decisions by big corporations amid national protests about racism.

The rebranding of popular products is nothing new, but many ask if it is enough? Quaker and its parent company PepsiCo have announced that they would also donate $5 million over the next five years to support African American communities.

“Companies have profited with billions of dollars and their only attempt is to get rid of the brand,” says Omari Souza, assistant professor, Communication Design at Texas State University. “They have profited off this negative stereotype (for generations). What responsibility do they have to the communities that they have impacted?”

Souza says his research explores the idea of perceptions, how visual narratives influence culture, and how we view ourselves and others around us.

“When we are born, we determine what relationships look like, based on watching our parents, watching television, and what we see in children’s books. As we grow, we have to hold on to these things,” he says. He explains that as children we understand that such images as stop signs and red lights have one meaning, but the images we celebrate, like cowboy films, might also demonize American Indians. “Looking at Disney cartoons, the heroines usually have western features, but the villains like Jafar from Aladdin or Ursula from The Little Mermaid tend to look ‘more ethnic.’”

Aunt Jemima, created more than 130 years ago to sell syrups, mixes and other food products, features an image of a Black woman that has often been linked to stereotypes around slavery. While the official web site for Uncle Ben’s Rice says the name and image are based on a Black Texas farmer, Mars Inc. said it was considering possible changes to the branding of Uncle Ben's, which entered the market in the 1940s. In a statement on its website, Mars said that "now is the right time to evolve Uncle Ben's brand, including its visual brand identity, which we will do."

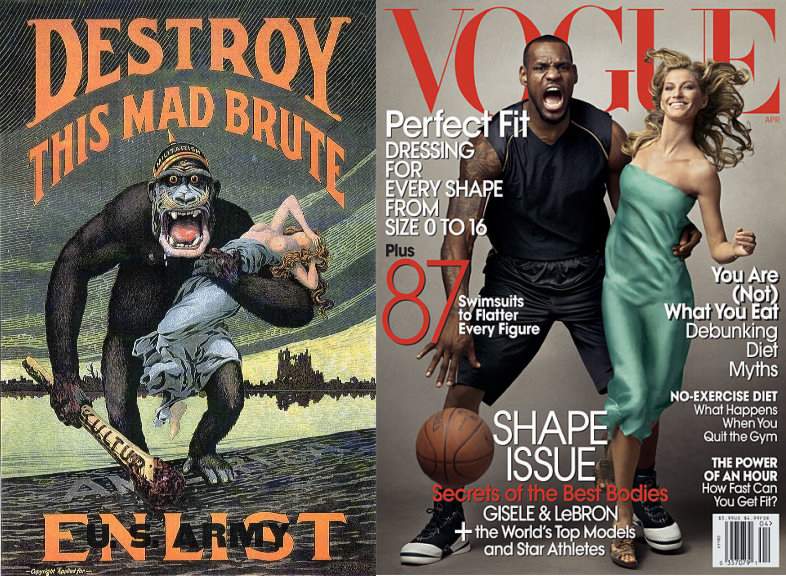

Souza points to advertising in recent years that has brought companies negative attention. “They kind of echo similar motifs of the past that have been used to demonize people of color,” he says. He singles out the fashion industry for such things as the “coolest monkey in the yard” T-shirt for children, or the Gucci blackface turtleneck seen on a runway model. In 2008 Vogue was accused of racism with its cover of LeBron James and Giselle Bunchen in what many people thought resembled a vintage King Kong poster. In 2019 the fashion house Burberry unveiled a hoodie with a ‘noose’ tie. In 2011 an ad for Nivea called “Re-Civilize Yourself” featured a well groomed Black man holding a decapitated head that had a full beard and afro. “It is hard to imagine,” Souza says. “I think it speaks to a number of things. It speaks to a lack of people in color in the decision-making process. I also think it is a lack of understanding of history.”

Souza uses the term racial capitalism -- the process of deriving value from the racial identity of others that harms the individuals affected and society as a whole. He said companies can release a diversity statement, but their actions don’t support bringing people into the decision making. “There are a lot of companies that are posting Black Lives Matter hashtags, then there are companies that I am impressed with -- like NASCAR, for banning Confederate flags, and for Sephora which has pledged that 15% of their inventory will come from Black- owned cosmetic companies.

Souza says he thinks it is exciting to see these stereotypical images going away, “but it isn’t enough when you consider the impact that the brands have on culture.”

“If anything, the brands have perpetuated inequality,” he says.

Souza is a first-generation American of Jamaican descent, raised in New York. Before coming to Texas State, he worked with such companies as VIBE magazine, the Buffalo News, CBS Radio, and Case Western Reserve University. He received his B.F.A. in Digital Media from Cleveland Institute of Art and his M.F.A. from Kent State University.

“My classes at Texas State are more diverse than any place I have taught,” he says. He teaches both undergraduate and graduate classes in the School of Art and Design.

“I don’t want to be a professor that is pushing students to believe in any particular thing. But I do bring into the classroom questions about ethics. Is this an ethical design? I talk to my students about whatever we create, we have a responsibility for it. Not to the person who initiates us to make it, but to the person that is going to see it.”

Souza recently presented “Images, Stereotypes, and Symbolism” at the Pivot 2020 design conference in June, sponsored by Tulane University. He also presented his work last fall at the International Conference of Visual Literacy Association conference in Leuven, Belgium. Souza recently completed an article for Blavity, a media company and website created by and for Black millennials. He is currently writing a book for Intellect books.

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |