Geography research on ‘community forestry’ in Central America leads professor to ugly underworld of international drug trafficking

Julie Cooper | November 20, 2018

When Dr. Jennifer Devine first traveled to Central America to study the Maya Biosphere Reserve, her goal was to learn about the successful development model of community forestry.

But what began as forestry research for this assistant professor of geography at Texas State has become a bigger lesson in narco deforestation and international drug trafficking. “The community foresters told me that the No. 1 threat to our social movement, and to this forest, are drug trafficking cattle ranchers. And I said, what do you mean they’re laundering money through livestock?

“What’s happening is that drug trafficking organizations are cutting down the forests and they are planting cattle pasture — not only so that they can launder drug money through cattle, but there’s over 100 airstrips in the Maya Biosphere and they are landing planes from the Andes full of cocaine and then it continues by land into the United States. It’s the equivalent of drug traffickers going into Yosemite National Park and cutting down the forest,” Devine says.

Currently, Devine’s grant project is focusing on drug trafficking and the impact on the environment and conservation governance. “Our research argues that the drug trafficking organizations are responsible for the majority of deforestation in Central America’s protected areas,” she says.

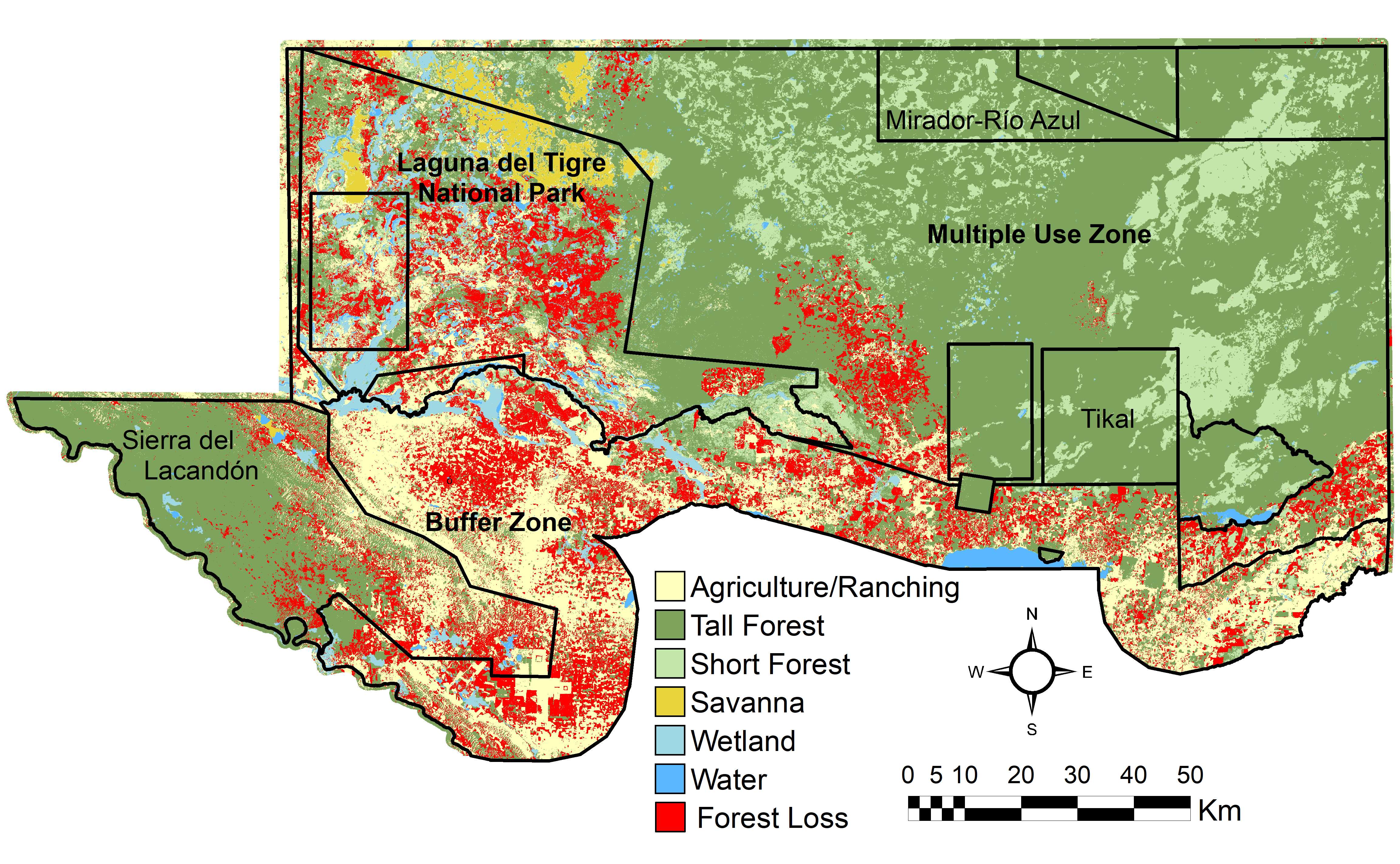

Her collaborative work with Texas State geographers Dr. Nathan Currit and graduate student Yunuen Reygadas suggests that cattle ranching is responsible for about 60 percent of the deforestation in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, which is a nature preserve, with some 50 percent of the reserve sharing a border with Mexico. In the 1990s, the architects of the Maya Biosphere put the national parks in the west, because it was the most sensitive ecologically, has many important archaeological sites, and contains scarlet macaw nesting grounds. The eastern part of the reserve was put into the hands of community members who are essentially guardians of the forest.

“Now the Maya Biosphere has the world's largest communally managed forest and it's kind of a global success story. It's so ironic because the other half of the reserve is heavily impacted by drug trafficking – so you have what I call a conservation paradox,” Devine says.

Devine explains that cattle ranching is an opportune industry for laundering drug money because there is very little control over the sale of cattle within Central America. “A drug trafficking organization that's trying to launder money through cattle ranching will spend $500,000 to buy 1,000 cows. They can then turn around and sell that cattle to legal Mexican meat producers and get a receipt. Within Central America, you can purchase cattle without a receipt, but once they sell any cattle back to Mexico they get a receipt and the money is laundered.”

The drug trafficking industry has also spawned markets in illegal timber, in people, and in antiquities. The people in the eastern part of the reserve are risking their livelihoods and lives to protect the forest. Devine says it is called “el plata o pomo strategy” — take the payment or the bullet.

She explains how it works: “A narco might come into that community forest because they’ve already taken over the national parks. They will tell a leader of the community forestry cooperative, ‘Sell me that land over there. I want to buy 100 acres of land.’ And the leader will say, ‘well you know, Mr. Narco I can’t sell you my land, I don’t own it. We have a concession from the state, if I sell this land illegally we would get kicked off.’ And he’ll say, ‘OK. I’ll come back in two months and offer your widow half the amount that I’ve offered you today.’”

One organization working to protect the region is the Association of Forest Communities of Petén. Devine calls the group “true conservation heroes” who are protecting what is left of one of the largest forests in Central America. “They make $18 million a year off the sale of mahogany. It's nothing like the money that can be made in the illicit industries, but with that $18 million they build schools, they pay for the teachers, they build health clinics and stock those health clinics. They're building a high school. Not to mention the fact that those economic benefits come in the form of salaries and good paying jobs with high skills.”

Devine believes that the U.S. War on Drugs has created a balloon effect throughout South and Central America. As the DEA, working with Colombia, shuts down one supply route, another route is shifted through Central America. “We are 40 years into it — $3 trillion dollars has been spent trying to stop drugs from coming into the United States. Hundreds of thousands of lives have been lost. The forests are being burnt. Democracies have been corrupted,” she says. “Drugs are cheaper and purer and are being used at a higher rate today than they were in the 1970s when Nixon declared the war on drugs. It is such a catastrophic failure.”

One solution that Devine suggests could be to stop funding militarized interdiction, or at least dramatically reduce militarized interdiction in Central America, and put the money into community development, public health programs and conservation organizations.

“If more money went into supporting organizations like community forestry in Guatemala, treating drug addiction, and reducing drug demand in the United States, that would be a path to really defeat the cartels. That’s the strategy that I think is the way to go,” Devine says.

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |