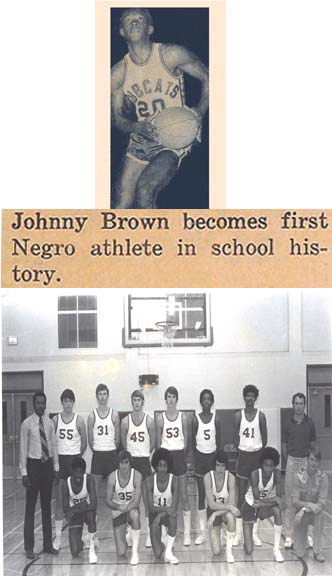

Dr. Johnny E. Brown remembers the challenges of being Texas State’s first Black student-athlete

Julie Cooper | September 9, 2021

Dr. Johnny E. Brown (B.S. ’70) remembers that day in 1966 when Coach Vernon McDonald sat on his family’s porch on Austin’s Emerson Street and told his parents why Brown should play basketball for the Bobcats.

Despite being recruited by several other colleges, including the University of Texas at Austin and some historically black colleges, Brown would select Texas State University and become its first Black student-athlete. He was also the only Black basketball player until the 1968-69 season when Perry Jackson joined the team.

“I was so humbled by that and appreciative of it. He (Coach McDonald) was the kind of salesman to express how much fun it would be and beneficial to attend college in San Marcos, become part of the team and graduate from there,” Brown recalls. “Frankly, we didn't discuss race and things like that. He admired my talents and skills and thought that I could contribute by being part of the team.”

At that time, Southwest Texas State was part of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics. McDonald explained to Brown that he would get a full scholarship including tuition, meals, and books — and $7 a month for laundry and incidentals.

These days Brown, 73, is an adjunct professor at Lamar University in Beaumont where he works in the superintendent certification program. He has served as a school superintendent in Texas, Alabama, Georgia, and as a deputy superintendent in Ohio. He has also written two books, The Emerson Street Story: Race, Class, Quality of Life and Faith and The Emerson Street Story 2: Winners Always Practice Program.

Last year, the Dr. Johnny E. Brown Committee on Racial Equality (CORE) was created to develop actionable recommendations to foster an inclusive culture in Texas State Athletics. CORE explores initiatives to strengthen education and development opportunities, promote voter registration and voting, and engage with the community regarding policing and relations. Brown is also active in community organizations like the Rotary Club and a group called 100 Black Men of Greater Beaumont.

“I am honored that Texas State University would think of me in that arena. It has to do with issues of diversity, equity inclusion, social justice, all of which are part of the CORE program. It was an area of my great interest and concern even back when I was in grade school,” Brown said.

Three years before Brown arrived on campus the first Black women students registered for classes. In February 1963 a U.S. district judge signed a court order to end segregation at the university.

“I did my little research. You could learn pretty quickly what the situation was,” Brown said. “This was during a time of segregation so the idea that I'd be going to what we considered a major university well, it wasn't a surprise. At that time, even up to and including the time when I graduated from high school, they would have concerts in downtown Austin where the whites would sit on the bottom floor and the African-American students and Hispanic students would sit upstairs.”

That first semester, Brown did not reside in the athletic dorm – it wasn’t integrated. He shared a room in Harris Hall with a Black student who practiced karate. By the next semester he was housed with the athletes. “The faculty and staff members were friendly, the players were friendly, and the coaches were certainly friendly,” he recalled.

But not all campus life brings back fond memories. Before there were rules against hazing on campus, freshmen student-athletes were subject to what some have called team building. Brown said it felt abusive. Upperclassmen would arm themselves with wooden boards, stopping to ask freshmen impossible questions, like ‘’what’s my mother’s name?” An incorrect answer would get the freshman a smack with the board.

“They called them 'warmups,'” Brown said. “If you complained the next day at practice the coaches would kind of turn their heads. I still remember how coaches would say, ‘hey, I know you don't like it, but this is part of becoming part of the team.’ ”

Then there were the road games when restaurants and hotels would not allow Brown and the team inside. “You can see the whispering — you know the coaches and managers — I didn't always know what they were saying, but you could tell by their blocking us at the doorway.

“We'd leave and go to another place and that part was tough and disappointing, but the players and the coaches were always supportive, understanding, and caring in their attitudes and we’d just move on,” he added. Brown recalled a game played at a Louisiana college whose players pushed him around and called him names. “The referees would laugh at it,” he said.

He remembered Texas State Athletic Director Milton Jowers as both strict and welcoming. Brown recalled the time Jowers said: “get that crud (mustache) from your face.” He also remembered a supportive Jowers. “He said to me that he thought I’d be a good educator and he thought I'd always work hard to be fair. He observed that I showed an interest in other people across different races and backgrounds,” Brown said.

Last year, the Dr. Johnny E. Brown Committee on Racial Equality (CORE) was created to develop actionable recommendations to foster an inclusive culture in Texas State Athletics

Brown earned his master’s degree in counseling and guidance at Texas State and went on to get his doctorate in educational administration at UT-Austin. His first teaching job was at a San Antonio middle school where he coached football, basketball, track, swimming, and tennis. He also taught physical education and biology/life sciences. He would progress to high school coaching and administration before joining the central office. Brown’s career would take him and his family to Cleveland, Ohio; Dallas; Houston; Birmingham, Alabama; and DeKalb, Georgia. His wife, Carolyn, is also an educator and they have three children: Berlin Lee Brown, Mary Katherine Brown Ruegg, and Reesha Brown Edwards.

“I had an interest and passion for working in places that were not doing well, so I searched those places out. Whereas some people go for the easy, highly successful areas to work in with no struggles, my attitude was 'if it's broken, I can help fix it,’ ” Brown said. He fixed school districts that were poorly performing or overspending. He didn’t make friends when he fired 50 teachers in one district or moved 20 administrators to schools that needed assistant principals.

“All these districts had all kinds of serious troubles. The good news is we were successful. Got them out of trouble, balanced budgets, increased test scores, built new facilities and did a lot of great things. But like climbing a mountain, you get a lot of dust all over you in the form of controversies because, obviously the idea of changing isn’t something they wanted to do,” he said.

When he was an undergraduate, Brown once saw President Lyndon Johnson during one of his visits to Texas State. Decades later, Brown would visit the White House with other school superintendents and tour the Oval Office with President George W. Bush.

“I give credit to my experience and Texas State University, by becoming prepared to be an educator and coach,” Brown said. “Being included with the athletes who became friends gave me a different outlook on life which I greatly benefited from throughout my career.”

Share this article

For more information, contact University Communications:Jayme Blaschke, 512-245-2555 Sandy Pantlik, 512-245-2922 |