Don’t Scream for Me, Krakatoa

Date of release: 12/12/03

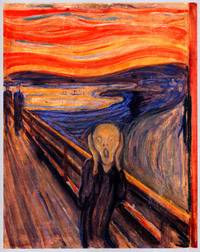

SAN MARCOS — One of the most cataclysmic volcanic eruptions in history may very well have inspired one of the most iconic paintings of the 19th century.

Through a combination of forensic astronomy and old-fashioned historical research, Texas State professors Don Olson, Russell Doescher and Marilynn Olson have not only determined where Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) stood when inspired to paint his anguished masterpiece The Scream, but that the lurid red sky triggering his inspiration was a direct result of dust and gasses ejected into the Earth’s upper atmosphere by the violent destruction of the island of Krakatoa half a world away. The team’s complete findings are published in the February 2004 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine.

Through a combination of forensic astronomy and old-fashioned historical research, Texas State professors Don Olson, Russell Doescher and Marilynn Olson have not only determined where Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) stood when inspired to paint his anguished masterpiece The Scream, but that the lurid red sky triggering his inspiration was a direct result of dust and gasses ejected into the Earth’s upper atmosphere by the violent destruction of the island of Krakatoa half a world away. The team’s complete findings are published in the February 2004 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine.

“I was actually looking at Munch’s Starry Night paintings, but kept coming back to The Scream,” Don Olson explained. “The sky in it looked like a Krakatoa twilight. I’m very familiar with the Krakatoa twilights, and my first reaction was, ‘That can’t be,’ because the first versions of The Scream were painted in 1892 and 1893, and Krakatoa erupted in 1883.”

Pursuing his hunch that the vivid sky was the result of a volcanic eruption, the team initially looked for good volcanic candidates that had erupted in the years just prior to 1892. But the looked-for eruption wasn’t there, nor were any records of spectacular sunsets. Instead, the team found that art historians had placed Munch’s twilight experience in a number of different years, some in the mid-1880s.

“Once we realized there was uncertainty, that the original experience could be in the 1880s, that opened up the possibility that Krakatoa was responsible,” Don Olson said.

Munch painted the most famous version of The Scream in 1893 as part of The Frieze of Life, a group of works derived from his personal experiences. The works in The Frieze of Life were painted in the 1890s, but many of them have established origins in the preceding decades.

Munch painted the most famous version of The Scream in 1893 as part of The Frieze of Life, a group of works derived from his personal experiences. The works in The Frieze of Life were painted in the 1890s, but many of them have established origins in the preceding decades.

“The majority of those paintings reflect experiences that happened to Munch many years earlier,” said Don Olson. “The death paintings are particularly clear. Death of the Mother and Death in the Sick Room, done in the 1890s, are based on the death of his mother in 1868 and the death of his sister in 1877. These experiences haunted him the rest of his life, as did the lurid, blood-red sky. So it is totally in character for Munch to be painting an event that happened many years earlier.”

While circumstance supported the team’s theory, they needed more facts to back them up, and that demanded the team make a research trip to Munch’s city of Christiania--modern day Oslo, Norway. In Oslo the Texas State researchers visited the Munch Museum, the National Gallery, the National Library and the Oslo City Museum on their quest.

“Munch left a wealth of paintings, drawings, journals, diaries, lithographs and manuscripts to the Munch Museum,” Don Olson explained. “Most of these materials are unpublished, so it was necessary to travel to Oslo to examine the materials. We wanted to verify the artist’s whereabouts in 1883-84.”

They found more than that--Munch’s papers from the archives at the Munch Museum and the National Library provided the “smoking gun” linking the time of The Scream’s inspiration to that of Krakatoa:

...the first Scream...Kiss...Melancholy....For these a number of rough sketches had already -- in 1885-89 -- been done in that I had written texts for them -- more correctly said, these are illustrations of some memoirs from 1884...

With the time frame of Munch’s inspiration narrowed down to a manageable window, the team began to refine this even further by determining when the Krakatoa twilights would have appeared in the Norwegian sky. Krakatoa destroyed itself on August 27, 1883, with the explosion being heard as far away as Australia and fading swells of tsunamis resulting from the blast reaching the English Channel. Reports from the Royal Society in London and the French journal Comptes Rendus show that the unusual “blood red” twilight spawned by Krakatoa had spread from the tropics to northern latitudes worldwide in the months following the eruption. The spectacular sunsets were visible in the higher latitudes of North America as well, impressing observers in Maine:

For several days past a striking and beautiful phenomenon has accompanied the sunset, and excited much comment. It is a blood-red coloring of the western sky, 10 or 12 degrees high, and appears just after sunset....The effect upon buildings of the reflected light was similar to that of red theatrical flames....

(New York Times, December 1, 1883)

By late November 1883, astronomers Carl Fredrik Fearnley and Hans Geelmuyden at the Christiania Observatory in what is now modern Oslo, Norway, first noticed a “very intense red glow that amazed the observers” which developed into a “red band.” The phenomenon lasted well into 1884.

Between November 1883 through February 1884, the crimson Norwegian sunset in the southwest would match perfectly the topographic features visible in The Scream and several other related paintings, allowing the Texas State team to conclude that Munch based his works on two observations points on Ekeberg hill--one from the historic road lined with railings and skirting the foot of the hill, and another from a rocky ledge 420 feet above, overlooking the harbor. The final, famous version of The Scream combines elements from both of these vantage points.

“One of the high points of our research trip to Oslo came when we rounded a bend in the road and realized we were standing in the exact spot where Munch had been 120 years ago,” Don Olson said. “We found the spot.

“It was very satisfying to stand in the exact spot where an artist had his experience,” he said. “The real importance of finding the location, though, was to determine the direction of view in the painting. We could see that Munch was looking to the southwest--exactly where the Krakatoa twilights appeared in the winter of 1883-84.”