SWT astronomers sleuth van Gogh “Moonrise” mystery

SAN MARCOS – Of all the works by Vincent van Gogh--and the Dutch master produced more than 2,000 paintings, drawings and sketches in his lifetime--the painting Moonrise has remained one of the most mysterious and enigmatic. Until now.

Astronomers at Southwest Texas State University have applied their unique brand of forensic astronomy to the puzzle, shedding new light on the celestial scene: Van Gogh painted Moonrise July 13, 1889 at the Saint-Paul monastery in Saint-Rémy, France. At 9:08 p.m., local mean time, to be precise.

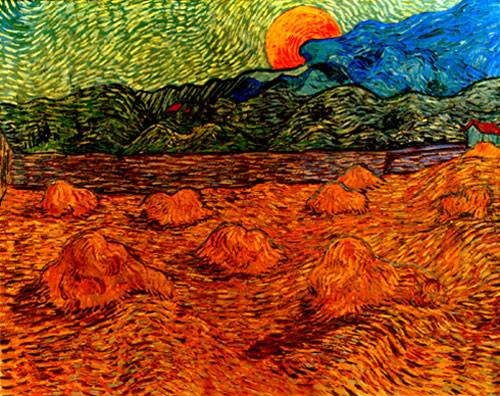

Image courtesy of Kroller-Muller Museum, The Netherlands.

Not bad, considering the piece was once mistakenly thought to depict the setting sun. SWT physics professors Donald Olson and Russell Doescher, along with English professor Marilynn Olson, published their findings in the July 2003 edition of Sky & Telescope magazine.

Art historians have long depended on van Gogh’s many letters to his brother Theo to date most of the artist’s work. But the only letter to mention Moonrise as a work “in progress” lacks a postmark or any other date reference.

“ Fortunately, the timeframe can be narrowed down significantly,” explained Donald Olson. Van Gogh painted the same wheat field many times while staying at the Saint-Paul monastery, and describes the view in letters to his brother. Van Gogh arrived at Saint-Rémy on May 8, 1889, and mailed the finished Moonrise canvas--along with nine other paintings, including the famous Starry Night--to his brother Theo in late September. That sets up a range of five months, but Olson suspected that astronomy could narrow the timeframe even further.

The painting itself turned out to be a goldmine of hints and clues. The moon is shown rising from behind a mountain range, partially obscured by an unusual overhanging cliff. The painting also shows an odd double house in the distance, as well a distinctive T intersection of two walls and in the foreground stacks of harvested wheat.

“If all we had was the moon, we couldn’t do much. It’s the fact that the moon was behind these very distinctive landscape features that’s key,” said Olson. “He painted those features not once, but over a dozen times. I can show you a dozen paintings with the T intersection and the double house. And you start thinking, this looks like this could be a real place.”

Indeed it was--and is--a real place. Traveling to Saint-Rémy in June 2002, Olson and his colleagues quickly confirmed that the view van Gogh painted from the monastery, complete with the overhanging cliff, did exist to the southeast. That fact, incidentally, reaffirmed the title Moonrise was the correct one for the painting--a sunset could only take place in the opposite direction. Beyond the monastery, a tall pine forest had grown up since van Gogh’s day, obscuring the view, but a little exploration soon uncovered the unusual double house featured in the painting, exactly where it should be.

Armed with this information, the team spent six days and nights observing the sun, moon and stars as well as calculating the distances and heights of the mountains and landscape features to determine precisely where van Gogh stood while he painted Moonrise.

“We can line everything up. The key is that the moon is behind that overhanging cliff,” Olson said. “If you just said, ‘When could Van Gogh have seen a full moon?’ well, there’s going to be one every month. But ‘When can you see a full moon rising behind that cliff?’ And the answer is not unique, but it’s only on two days.”

After consulting lunar tables and astronomical software, only two possible nights offered a full moon passing behind the cliff--May 16 and July 13. And again, van Gogh’s own work provided the final clues to the puzzle.

“ The moon aligned with the cliff both nights. Then you see the harvested wheat in the painting, so it can’t be May. He has two paintings of that field in May, and they’re lush green. By June, you’ve got the yellow field The Reaper,” Olson said, referring to the harvest painting featured prominently in the 1956 movie about van Gogh, Lust for Life.

Because van Gogh rarely painted from memory and preferred to have his subject in front of him, the wheat stacks in Moonrise follow perfectly the progression established by his painting of green fields in May and the harvest in June, leaving July 13 as the only possible date for the creation of Moonrise. And after a few more astronomical calculations, they could pinpoint exactly when the moon would rise past the cliff: 9:08 p.m., local mean time.

“ On July 13 the moon rose right behind that overhanging cliff,” Olson said. “The night before and the night after, it would not align with the cliff. We can absolutely tell which date it is.

“ The moon only spent two minutes passing behind the cliff, so if you take it centered, your error is less than plus or minus one minute,” he said. “Van Gogh would have seen exactly what’s in the painting at exactly that time.”

Timing is everything, as they say, and sometimes the arts and sciences fall into synch. In 2003, the Netherlands celebrates the 150th anniversary of van Gogh’s birth, while at the same time, the progression of 19-year-long lunar Metonic cycles coincides with that of 1889--meaning that skywatchers in Saint-Rémy are in for a celestial encore.

“This is the year of van Gogh, and this year on July 13, there will be a nearly full moon rising in the southeast in the evening twilight, recreating the evening sky van Gogh saw back on that night in 1889,” said Olson. “Isn’t it nice the way things fall into place?”

Contact: Don Olson at (512) 245-2131